Avant a clue

Peter Carty’s satirical look at the art world in Hoxton is both zany and poignant, says Olly Gruner

Thursday, 29th February — By Olly Gruner

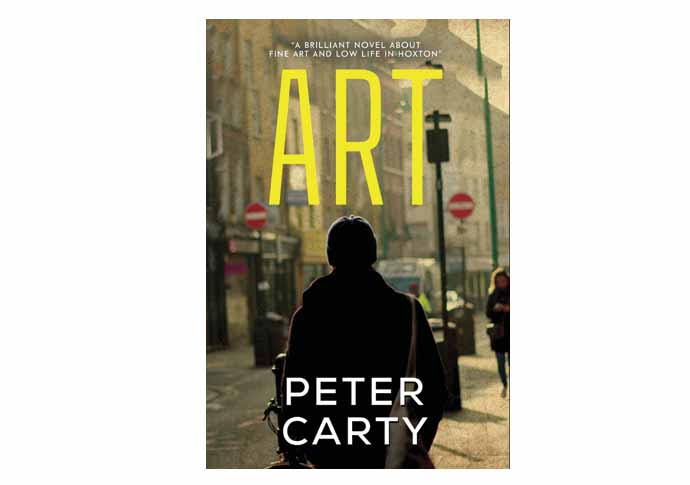

Peter Carty, author of Art

FEARSOME excess and loathsome egos collide in Highbury resident Peter Carty’s debut novel Art, a blistering satire about Hoxton’s art scene of the early 1990s.

Set in a pre-gentrification East End, before the hipsters and tech crowd arrived, Art evokes the creative and social milieu from which emerged the “Young British Artists” (or, as they were immortalised in acronym, the YBAs). If the likes of Tracey Emin and Damien Hirst have been replaced by Carty’s own fictional creations, the novel is nonetheless as rich on historical atmosphere as it is on dark humour and rhetorical flair.

Carty, a journalist, was living in Old Street at the time of the novel’s action and moved in the same circles as many of the artists and curators then rising to prominence. “Everyone felt we were at the start of an enormous cultural moment,” he says. “You could compare it (albeit loosely) to London in the Swinging Sixties or the Left Bank in Paris during the 1920s.”

Not unlike these avant-garde enclaves of years gone by, the area described in Art is a place where creativity comes up against the forces of commerce, and visions of bohemia belie pervasive social and economic inequalities.

The narrative revolves around an assortment of artists, curators and collectors on the cusp of fame. From the off, we are sucked into a hedonistic whirlwind, meeting Alistair Given, “visionary” director of the gallery Idiot Savant, as he presides over a cocaine binge (very much a sign of things to come).

There’s the rising superstar artist Kevin Thorn – nihilistic, adept at a provocative publicity stunt, schmoozed at every private view as if he were, in Carty’s characteristically pungent phrase, “a prize marrow being painstakingly anointed with liquid manure”.

Characters like Becky Edge, whose video art garners much attention for its “playful use of signifiers of domesticity”, Tania Russell-Smith – outspoken, a loose canon – and Erick Heckendorf, famed for his “installations about nothing”, provide opportunity for exploring and, often, parodying, the era’s pretensions. Jargon-heavy “art speak” and art theory are referenced in cod-philosophical chapter titles (“Discrete Entities Moving in Similar Directions in Search of Mutual Comprehension”) and humorous subtexts.

Looking on from the sidelines is art journalist Billy McCrory – ever searching for the ultimate scoop, ever loaded on narcotics – whose off-kilter perspective on events sometimes makes him seem like a kind of drug-addled Nick Carraway, narrator of The Great Gatsby.

For all its comedic exuberance, Art also offers some penetrating commentary on societal transformation. “The YBAs positioned themselves as rebels,” says Carty. “Though of course in reality they’d almost all been to art school, most often to the top art schools – St Martins and the Slade – and many of them were privately educated.”

There is a sense that the artists in this novel are interlopers, their colourful antics unable to paper the cracks of a divided community. Class conflicts imbue character relationships and dramatic sequences throughout. While hipsters move into the area and ludicrously rich collectors suck up as many artworks as possible, the East End’s gentrification pushes poorer residents further onto the outskirts or deeper into poverty: “The only trickle down from hipsters was the bodily wastes swamping the decrepit sewers under their overpriced lofts.”

Furthermore, the artists ply their trade on streets where organised crime and political extremism are rife. The far-right British National Party was headquartered in Shoreditch High Street until the late 1980s and, recalls Carty, there were still “active fascists in the areas in the early 1990s.” The world of Art is no bohemian paradise but, rather, a complicated landscape in the throes of upheaval.

Today, with skyrocketing rents and a cost-of-living crisis, such critique remains relevant. Art speaks to the ceaseless march of gentrification since the 90s – from the trendy bars to the Silicon Roundabout – and the growing gulf between rich and poor. “There’s a huge amount of dilapidated social housing in that area and local people stay on minimum wages or no wages at all”, says Carty. “They haven’t had the benefit – most of them – of the insane property price inflation or the plum jobs in tech.”

In a more general sense, I was struck by the novel’s multi-layered structure: its ability to shift between various perspectives, time periods and registers. Carty told me that writing Art was “like building a house on your own without any architect’s plans, or indeed any definitive plans of your own. Halfway through you realise the foundations need adjusting, so you have to rip a chunk of the building down and build it again.”

All the more remarkable, then, that it maintains its rambunctious energy throughout.

Brimming with satire and packed with contemporary resonance, Art is a brilliantly zany, poignant piece of work. It does a fine job memorialising (where due) and satirising (where needed) this important, but ultimately fleeting, moment in British cultural history: “a glimmer before the fade back to grey”.

• Art. By Peter Carty, Pegasus, £10.99.

• Peter Carty will give two free talks on how he researched and wrote Art, which will include tips for budding authors, at 6.30pm on March 7 at West Library, 107 Bridgeman Road, N1 1BD, and at 6.30pm on March 26 at Swiss Cottage Library, 88 Avenue Road, NW3 3HA.

• Dr Olly Gruner is a Senior Lecturer in Visual Culture at the University of Portsmouth.