Bound to please: How ‘Handcuff King' Harry Houdini inspired new children's book

Harry Houdini would have been 150 this week. Julie Carpenter looks at the life of the illusionist who inspired her new book for children

Thursday, 28th March — By Julie Carpenter

Julie Carpenter, author of Harry and the Highwire

HE was, in the words of Derren Brown, “the greatest magician who ever lived”. At the height of his fame, legendary illusionist Harry Houdini was the highest paid entertainer in the world and, exactly 150 years since his birth, his name is still a byword for a miraculous escape.

It is hard to over-emphasise the size of the crowds that would throng to witness his death-defying escape acts.

When he announced in November 1908 his intention to perform one of his celebrated manacled jumps off London’s Westminster Bridge, the Metropolitan Police so feared the chaos that would be caused by thousands of spectators jostling to see whether Houdini would escape his fetters or drown, that they intervened to prevent the stunt going ahead.

But when Houdini first came to London from America in June 1900, suffering acute seasickness on the voyage over, it was a different story. While he’d gained moderate fame in the US, here he had no manager and no bookings.

Undaunted, he settled himself and his wife Bess into a modest boarding house in Bloomsbury’s 10 Keppel Street, and set his sights on performing at the impressive Alhambra Theatre in Leicester Square.

The manager, Charles Dundas Slater, insisted Houdini audition before signing him.

Houdini at this time billed himself as the “Handcuff King” and claimed he could escape from any fetter. Slater duly whisked him off to Scotland Yard. There, he was reputedly clapped in the police superintendent’s most secure restraints but freed himself so easily he landed his career-making booking at the Alhambra and sold out the venue for months.

Over the next 20 years, Houdini would bring his most sensational escapes to the UK, including the infamous Chinese Water Torture Cell. Here, he was suspended upside down and shackled in a glass cabinet filled entirely with water. His posters warned: “Failure means a drowning death!” and assistants would stand on stage with axes ready to smash the glass in case the escape went wrong.

It never did – but London was also the scene of one of Houdini’s most testing stunts. While performing at the Hippodrome in March 1904, a Daily Mirror reporter leapt on stage and challenged him to escape “the most difficult handcuffs ever invented”. They had taken a Birmingham blacksmith five years to make and Houdini emerged victorious – but only just.

After over an hour of struggle, he was left drenched in sweat and according to one newspaper account, “hysterical and weeping”. Afterwards told a friend he’d “sooner face death a dozen times than live through that ordeal again”.

Facing death, however, is exactly what Houdini did night after night, forever upping the ante. He wrestled free from handcuffs and straitjackets while dangling precariously from 400ft high skyscrapers, while plunged into icy rivers or while buried alive.

Exactly what drove him to go to such extremes is still much debated but Houdini certainly recognised the powerful lure of watching something that could go disastrously wrong at any moment. It was something he first experienced as a seven-year-old boy.

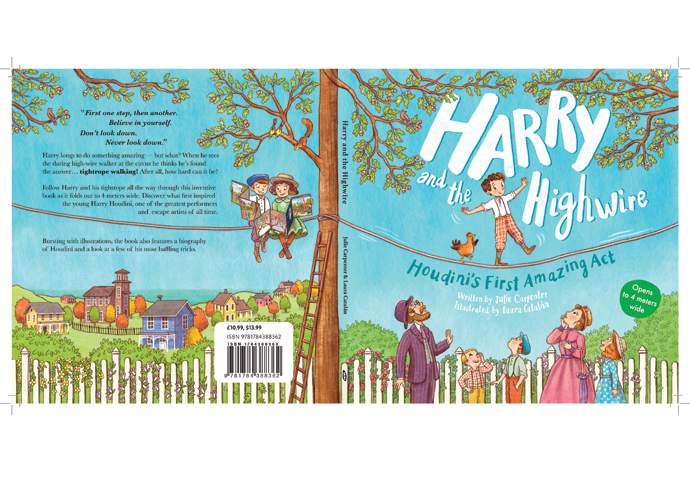

That moment features in my new children’s book, Harry and the Highwire. It’s a lighthearted story about what inspired the young Harry but that early inspiration is also arguably what lit a flame in Houdini that burned until his death in 1926.

Houdini had come to the US from Hungary in 1878 as a four-year-old, the immigrant son of a rabbi. Then known by his real name of Ehrich Weiss, he visited a travelling circus and was spellbound by the highwire artist, Jean Weitzman. In the words of biographers William Kalush and Larry Sloman, he found the idea of someone risking their life right in front of him,“both inconceivable and thrilling”.

He went home and immediately attempted to learn the same skills, displaying a level of dedication and perseverance far surpassing his years. By the age of nine, he was performing a trapeze act in the Jack Hoeffler circus.

Houdini was nothing if not committed. Supremely athletic, he taught himself multiple skills including how to manipulate individual muscles of his body, how to untie knots with his toes and how to hold his breath underwater for three-and-a-half minutes. He collected and examined locks in exhaustive detail, obsessively studied magic and practised every single day. And, perhaps most importantly, he taught himself the mental art of how not to panic while under extreme stress.

To what end? I’d argue that ultimately, Houdini wanted to be extraordinary, to stand out from the crowds and inspire that same sense of awe he experienced as a child – only magnified.

“I want to be first. I vehemently want to be first,” he once admitted. “So I have struggled and fought. I have done and abstained; I have tortured my body and risked my life only for that.”

Many would say he achieved it.

• Harry and the Highwire. By Julie Carpenter and illustrated by Laura Catalan, Green Bean Books, £10.99