But is it art?

Was Duchamp taking the p*** with his Urinal? In his memoirs, Julian Spalding takes conceptual art to task. Dan Carrier reports

Thursday, 14th December 2023 — By Dan Carrier

Julian Spalding with gallery owner Rebecca Hossacks

IT is not more than a couple of generations ago that British art was producing sculptors like Gilbert Bayes and painters like Frank Auerbach.

These were craftspeople who had not just something to say but poured days into perfecting their skill, and filled their nights with dreams of what they hoped to achieve.

It is a far cry from the art of the Young British Artists (YBAs) – conceptual work that is idea-led, rather than a piece created by a mixture of an individual’s spatial awareness, their motor skills combined with imagination.

Art Exposed, a memoir by gallery director Julian Spalding, comprehensively skewers the art world today and takes apart the links between dealers, galleries and public bodies.

Through this story of a life in galleries and museums, of meetings with artists and historians, Julian reminds the reader what constitutes great art. And importantly, he shows why it isn’t purely down to your personal taste.

He calls on us to be “ambitious” for the art we produce today.

“Why should other ages have Botticelli and Bosch, Velázquez and Goya, Picasso and Matisse, when we’re supposed to be content with a shark in a tank, a soiled bed and a can of shit (literally – one was bought by the Tate)”? Of course great art is being made now – it has to be, among seven billion of us it’s just that the curators responsible for showing it have to search hard and wide to find it.”

Born in 1947, Julian grew up in south London. He was raised on a council estate and believes this beginning has stood him in good stead to deal with some of the pretensions he has encountered in rarefied arty air.

A fine art and art history graduate, he has been the director of art galleries in Sheffield, Manchester and Glasgow. His work includes establishing award-winning museums including the Ruskin Gallery, the St Mungo Museum of Religious Art and Life, Glasgow’s Gallery of Modern Art and the Open Museum.

Julian moved on from museums in 1999, and has since turned his hand to writing books and running campaigns to increase access and improve standards.

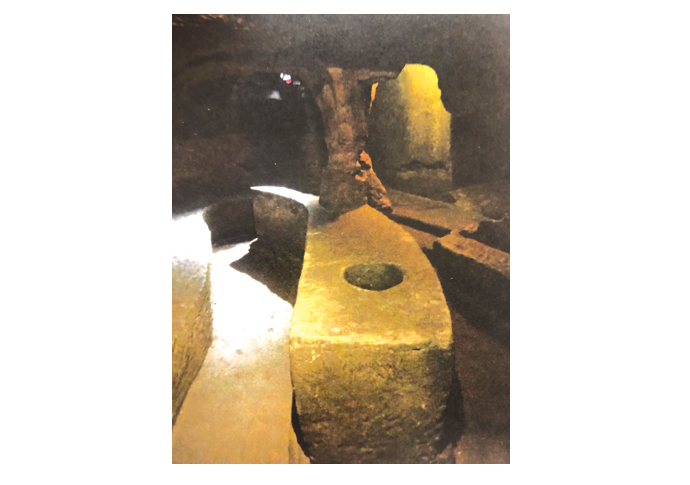

Gilmerton Cove

His no-nonsense assessment of the emperor’s new clothes approach of the YBA movement was evident in his critique Con Art – Why You Should Sell Your Damien Hirsts While You Can back in 2012.

They are topics he returns to here.

“I look back and I get so bewildered. I walk round Tate Modern and I think – what the hell is all this? What has happened? I wanted to look at that.”

The memoir is set out in chapters running from A-Z. It is not a linear story – rather a series of musings on people and places that have moved him one way or another.

“I did not want to be at the centre of my memoirs,” he explains.

“I am writing about things that have interested me, not about myself. I don’t want to go on some ego trip. I wanted to think of the artists and the people I have met.”

Julian has long championed fine art, no matter what era it was created. It has pained him to watch the craft decline over 40 years. He asks why.

“It has to do with money,” he says. “To develop a craft takes time and equipment.

“To paint you need canvas, easels, brushes. To sculpt you need stone and chisels. It is expensive to run technical art schools. When the idea of conceptual art came about – focusing on ideas not creation through craftsmanship – administrators loved it. It was relatively cheap.

“Students were told to spend a year thinking about art when they should be painting, drawing and making things. Without the craft, the ability to make, the physical creation side, has gone.”

He has watched aghast as the foundations of our shared visual language has been hijacked by money-making nonsense.

“The contemporary scene, pushed by the art establishment, is what I call Con Art,” he adds.

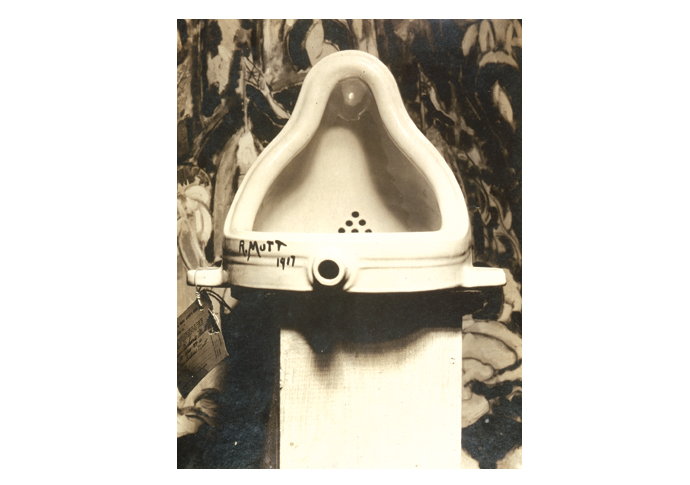

Under D for Marcel Duchamp Julian explains in detail how wrong-headed the contemporary acceptance that anything can be art if the viewer wishes it to be. He cites the artist’s “Urinal” piece as a perfect example of “dull and puerile” works.

Marcel Duchamp’s Urinal [Alfred Stieglitz]

Julian cannot restrict his love of a creative process to things you can hang on a wall.

M is for archaeologist Euan Mackie, and Julian begins with an unexpected aside: the story of how he believed he had seen a ghost.

“I was cycling to school when I was about 12,” he writes. “An old man was cycling in front of me, wearing a long raincoat. We came to a corner but he went on straight ahead and disappeared through a brick wall.

“I must have imagined him, of course, but in that moment, I was sure I had seen a ghost.”

From here Julian introduces a truly remarkable story: he was accompanying his wife, Gillian Tait, as she researched a book about Edinburgh. She took him to a carved-out underground chamber called Gilmerton Cove.

It was believed to have been hollowed out by a George Paterson in the 1700s for a pub.

What Julian saw as he stepped inside made the hairs on the back of his neck stand up, reminding him of the ghostly bike rider he saw many years previously.

He describes the work supposedly undertaken by the solo Mr Paterson – and immediately doubted the story.

Struck by Celtic imagery, intrigued by tunnels back filled with rubble, he brought archaeologist Euan Mackie on board to investigate.

Euan believes the caverns are an ancient Druid temple, and radar work above background has shown just how far they stretch. But Julian could not get Edinburgh City Council to take up interest in what he says could be an Scottish equivalent of Stonehenge sitting beneath their feet.

“This is a story waiting for an ending,” he says. “The evidence is staring everyone in the face. But it is so strong and unusual that hardly anyone can see it. It is an artefact in itself, created by a team of carvers individually as skilled as Michelangelo working to an equally imaginative vision in their minds. Gilmerton Cove, when seen for what it is – a profound and fascinating work of art – if Euan and I are right, it will change the history of Europe.”

• Art Exposed. By Julian Spalding. Pallas Athene, £10