Oar-inspiring: the original boat race

On this week’s virtual ramble, Diary dips into Thames history, recalls a daring prison break, and enjoys one of Ben Pimlico’s ‘nut browne’ ales

Friday, 17th July 2020 — By The Xtra Diary

The finish of the Doggett’s Coat and Badge rowing race, by Thomas Rowlandson

YOUR Westminster Diarist has not quite gathered the strength to venture forth, so from the comfort of our perch and with a fresh page in front of us, let us continue on our virtual tour of this splendid borough we call home.

We departed last week at the bottom of King Charles Street, gazing out at the river, and remembering the time in 1909 a pig flew past this very spot.

From our vantage point, let us first speak of the oldest continuous sporting event in the country, in which the Thames plays a crucial part.

While the annual, brawny-shouldered, gin-and-it-soaked Oxford and Cambridge boat race enjoys both longevity and global fame, there’s another that pre-dates it. It goes under the delightful name of the Doggett’s Coat and Badge race.

Thomas Doggett, an actor of Irish descent who was to become the manager of the Drury Lane theatre, established the event in the 1710s. Taking place on August 1 each year, it required oarsmen to scull their way from London Bridge to Chelsea, with the winner receiving a new coat and a silver badge.

It is said Doggett wanted to say thank you to the Thames watermen after one rescued him from the waters after he was returning home late one night from the theatre. He even left money in his will to guarantee it continued after he had departed this mortal coil.

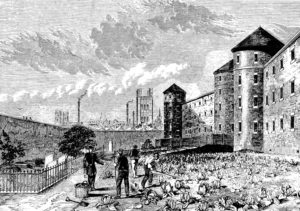

Millbank prison – built in the Napoleonic era, it had a reputation for harshness

Sculling against an ebb tide must have been exhausting, and it is the Thames’ tidal reach of 60 miles that helped power industries along its Westminster banks.

We are by Millbank, whose name recalls the presence of watermills – the last of three was demolished in the early 1700s, around the time Doggett was watching his oarsman fly past.

One hundred years later, Millbank was the site of the largest prison in Britain. Built during the Napoleonic period, completed in 1821, it used a revolutionary design that housed prisoners in a circular building with a central point that could be used to observe them. Eventually demolished in 1890, it earned a reputation for harshness.

It was, however, the scene of a daring escape by one Martin Sheen in 1864, as reported in the pages of The Launceston Examiner.

Sheen, 28, described as five foot tall with iron grey hair and hazel eyes, a broken nose and broken right hand, labelled “stout” by his gaolers, was a surgeon by trade. He lived in Wardour Street for many years until he fell foul of the law – and earned himself a 10-year stretch for forgery.

Following his conviction, he was first incarcerated at Pentonville, but following an escape attempt was transferred to the more secure Millbank.

After serving 18 months, he decided it really wasn’t the life for him and was caught making more than a dozen flits.

Eventually, he cracked it: Sheen had managed to keep a knife about himself, despite regular searches, and used it to chisel away bricks in the corner of a cell on the top storey of the circular prison block. He made a hole large enough to squeeze through, and then lowered himself down 88 feet on a coconut fibre rope, made from matting stolen from the chapel. On one end was a hook fashioned out of a tin cup, and Sheen used it to circumnavigate a number of walls and roofs inside the prison.

Eventually he ended up in a garden after scaling a 20ft boundary wall care of a weighted sandbag to hoik his rope over.

The Examiner said: “For coolness of execution it has hardly been surpassed. Utmost vigilance is being paid to recapture the convict, but he is not known as a regular offender, of course the difficulty of recognition becomes increased…”

Sheen was last seen scarpering westwards along the banks of the Thames, and we shall follow in his footsteps until we come to Tate Britain.

Here, we shall remember the bitter winter of 1927.

That year, London experienced a very white Christmas. It started on Christmas night and by Boxing Day had developed into a blizzard. There were six inches of snow across Westminster, and then came fierce gales that caused huge snow drifts. Roads, cars – all hidden beneath a huge white blanket.

But worse was to come.

On New Year’s Eve there was a thaw, followed by rain storms of such severity they had not been seen for a generation. Furthermore, a North Sea gale whooshed up the Thames, giving it its highest tide in 50 years.

In January 1927 the Thames paid the art gallery a visit. Swamping the building that housed sugar magnate Sir Henry’s collection, a nightwatchman had to swim through submerged corridors to escape, and a set of Turner’s drawings were ruined.

And it is now we find ourselves in Pimlico, and let us pause to consider this well-heeled neighbourhood’s connection with the more rough and ready Hoxton, out east.

Ben Pimlico was a publican in that neck of the woods and became celebrated for a “nut browne” ale he brewed.

A boozer near what is now Victoria station opened in the 1620s and decided the famous brewer’s surname would make an excellent moniker. Whether Ben had any say in this matter has been lost in the mists of time.

And his surname, which would come to mean the entire area, is said to have derived from a tribe of Native Americans encountered by Sir Walter Raleigh in the 1580s.

According to legend, an adventurer accompanying Sir Walt was given “Pimlico” as a nickname, such was his interest in the women they encountered in this group – and is said to have been the father of Ben.

And on that note, we shall leave you for another week. Stay well, and stay safe.