Fellow creatures

Anna Lamche samples the sights and sounds at the British Library’s major new exhibition drawn from historic archives documenting the animal kingdom

Thursday, 27th April 2023 — By Anna Lamche

Illustration from a book on veterinary medicine, annotating the parts of a horse [The British Library]

IN 1983 the conservationist John Sincock travelled to the island of Kauai as part a of a survey of the birds living in the Hawaiian archipelago.

There Sincock recorded the soft, richly melodious mating call of a male Kauai O’o A’a, a small, honey-eating songbird.

A species decimated by deforestation, this male was the last O’o A’a bird on Earth: his mate had died the previous year and would never answer him again. Shortly after the recording was made, the male O’o A’a disappeared too, and his species passed into extinction.

Preserved in the sounds archive of the British Library, this haunting song can be heard in Animals: Art, Science and Sound in the library’s PACCAR gallery. It is one of the many moving moments in an exhibition that demands we pause and take note of the world’s wonders before they disappear.

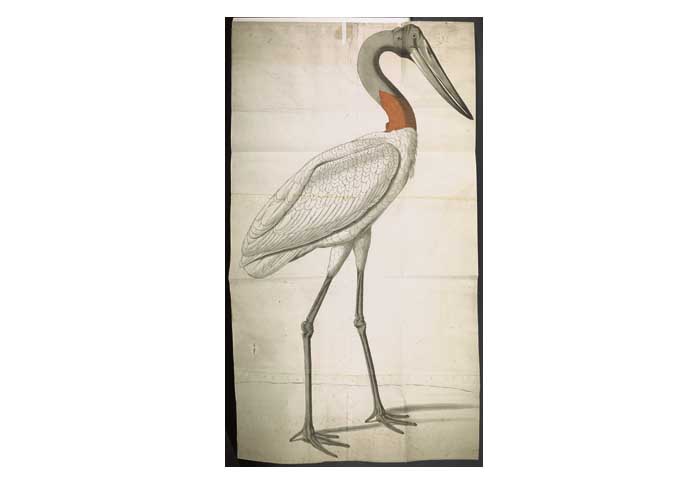

Illustration of a South American Jabiru, before 1820. Artist unknown [The British Library]

According to co-curator Cam Sharp-Jones there was a fine balancing act involved in putting the exhibition together. “We wanted to balance it so that it wasn’t an overwhelming narrative – we want people to come away being very inspired by the natural world and by animals,” she said.

Drawn from the copious wildlife and environmental collections stored at the British Library, the exhibition is the result of three years of work by Ms Sharp-Jones and her co-curators, the sound archivist Cheryl Tipp and visual curator Dr Malini Roy.

They came across many creatures either endangered or extinct during their research. “There were those days when you were doing all this research into these animals, and you felt quite low,” she said. Other days were more hopeful, as they discovered “absolutely amazing” material in the archives. “There were a lot of moments of stunned silence,” Ms Sharp-Jones said.

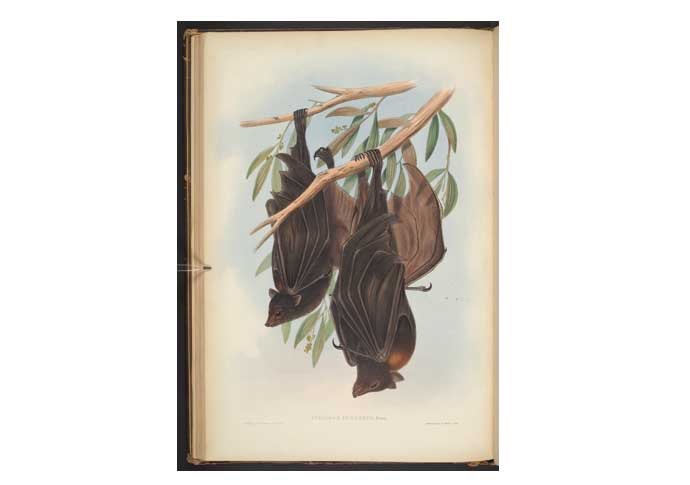

The end product is a rich mixture of visual art, manuscript and sound, coalescing around four zones: darkness, water, land and air. This structure “allowed us to have flexibility to look at the diverse material we have,” Ms Sharp-Jones says. Visitors see and hear bats, sharks, squids, horses, insects, frogs and birds inhabiting in “completely different worlds” to those encountered by humans.

Field sketch of a red panda by an unknown artist for Brian Houghton Hodgson [The British Library]

Emerging from the exhibition is a picture of animal life as something splendidly intelligent and strange. Each creature has a “different way of sensing the world,” Ms Sharp-Jones says, inhabiting “worlds that we don’t really experience in the same way.

“We’re still definitely learning about animals. That’s one of our key messages: we know quite a lot, but every day we learn there’s something new about these creatures that we share the Earth with.”

In his book Ways of Being, published last year, artist and writer James Bridle calls on his readers to appreciate the “many different intelligences” embodied in animal and plant life.

“Until very recently, humankind was understood to be the sole possessor of intelligence. It was the quality that made us unique among life forms,” Mr Bridle writes. “It’s a trick of the light of course: these other minds have always been here, all around us, but Western science and popular imagination, after centuries of inattention and denial, are only just starting to take them seriously.”

Bats illustrated in John Gould’s, The Mammals of Australia, 1845-63 [The British Library]

Perhaps the British Library’s exhibition is indicative of a broader cultural shift in the way we perceive and engage with the natural world. The historic manuscripts and ancient paintings on show reveal that the story of humanity is, in the words of Mr Bridle, the story of “our utter entanglement with the more-than-human world”.

The power of narrative is another key theme threaded through the exhibits. The stories we tell ourselves about animal life can destroy or save a species. Peter Benchley’s Jaws is highlighted as an example of the negative potential of fiction, a work largely responsible for the way sharks are maligned as “mindless killing machines,”says Ms Sharp Jones.

“Our current understanding of sharks is completely filtered through the media,” says sound archivist Ms Tipp.

Meanwhile, Songs of the Humpback Whale, an LP released by Capitol Records in 1970, allowed environmental campaigners to tell a story about the importance of saving the Earth’s largest mammal.

An illustration of an adult and juvenile Kauai O’o A’a (Moho braccatus), now extinct, by JG Keulemans (1842–1912) [The British Library]

“[The LP] played a massive part in the ‘save the whales’ movement in the 1970s,” Ms Tipp says.

“Because it’s really emotive, they were able to use that to get public support and political support. It’s very mournful. And it played a huge part in bringing an end to commercial whaling.”

One of the most beautiful items on display is artist Alicia Bailey’s book Evanesco – A Selection of Beleaguered Frogs. The artist found a set of her great aunt’s undergraduate biology notebooks, created in 1920, and painstakingly painted a variety of endangered frogs over the top.

A comment on the gradual way human knowledge accumulates, during the making of the work Ms Bailey was preoccupied by several burning questions: “Blake believed that the object of being human is to learn how to be human. Will we learn to be human in time? To live up to our full capacities in time to save ourselves? To save the world that is vulnerable to us?”

These are also the urgent questions the exhibition asks of its visitors. In the words of Ms Bailey, “to fail will bring on a greater tragedy than we can possibly imagine”.

• Animals: Art, Science and Sound runs until August 28. The British Library, 96 Euston Road, NW1 2DB, adult tickets £16, concessions available, 01937 546546, www.bl.uk