Firth among equals

Posthumously explored notebooks and letters led Hugh Firth and Loulou Brown to a story of parental infidelity that now form the basis of a book filled with love and secrets. Dan Carrier spoke to them

Thursday, 28th March — By Dan Carrier

Raymond Firth and Rosemary in 1978

BEFORE anthropologist Rosemary Firth died in 2005, she told her son he would find some letters and notebooks “that may be of interest”.

But this was not a handful of cherished love missives or a youthful diary. It was a 60-year story told through more than three million words – and within the many pages, long-held secrets emerged.

When Hugh Firth settled down to read through his mother’s writing, he discovered she had never fallen out of love with a young man she met in the early 30s, Edmund Leach.

And while Rosemary had married another anthropologist, Raymond Firth, Hugh’s father, she and Edmund had conducted a sporadic affair for decades.

When Hugh realised this was the case, he contacted Edmund’s daughter, Loulou Brown, and said he had some letters she might want to read. The result is a book based on Rosemary’s words.

“I became aware of these notebooks before her death,” says Hugh. “She told both myself and my sister that we may want to read them.”

Loulou and Hugh met at Hugh’s mother’s funeral. Although they had occasional met when they were children, they had not spoken for 30 years and the reunion was the crucible for a personal story of their parents’ enduring love while married to others.

Drawing on diaries stretching over seven decades and a similar cache of letters, Loulou and Hugh have traced how their parents met, and how their life-long relationship unfolded.

“My mother was a frank talker,” recalls Hugh. “I did know my parents well, and that is why I was so astounded.

“They were hidden in plain sight, my father’s affair with a younger anthropologist and my mother’s with Edmund, and then a friend called Helen – individuals I knew and liked.”

LSE professor Raymond Firth is considered to be a founding father of modern anthropology, and remained married to Rosemary for 65 years.

“Inevitably this story is told through one particular lens, although it is supplemented by our knowledge and memory of details of our parents,” say the authors.

Rosemary was 16 when she met Edmund, 17.

“They were both extremely bright, from families that discussed politics, ethics, literature, philosophy and religion.

“They shared an interest in big ideas, but above all a belief in the virtue of being frank and honest, both had a strong distaste for insincerity of any kind,” say the authors.

“They had a romantic side. Rosemary had already developed a lifelong love of Elizabethan verse, and poetry served as another means of communication and understanding.”

Edmund Leach and Rosemary Firth in 1931

Rosemary was living in the family home in Bishopswood Road, Highgate – and saw Edmund off on a train to Germany in August 1931.

She wrote: “I had wandered mechanically off Victoria station, wondering how on earth I could get home without bursting into tears.”

Rosemary headed to Edinburgh University. They remained pen friends but while an engagement had hung in the air, it was not forthcoming. Rosemary decided, as Edmund finished his finals, to call time.

A final meeting went so badly that Gilbert, Rosemary’s father, told Edmund he must not contact her again.

We learn of a friendship with a student called James Livingstone that helped ease the pain – but when Rosemary sent a letter of condolence when Edmund’s father had died, the relationship was rekindled.

They spent a happy summer together before Edmund took a job with trading company Merchant and Squire – a position in China – for four years.

Rosemary hoped for an engagement before he left: instead, she got a letter.

“My love, do try to understand – we were not meant for each other,” he wrote.

“Take it then thus and set it in your bosom, the full flushed rose in all her ecstasy. I beg you do not wait until the petals curl and fall away.”

Edmund did not return until 1937, and by then Raymond and Rosemary were married.

Raymond, on the fringes of the Bloomsbury Set, counted RH Tawney and William Beveridge as friends.

In 1928, he spent a year on the island of Tikopia. His account, published in 1936, remains in print and is a key work for anthropologists and a record for the people of Tikopia.

When Edmund reappeared, she introduced Raymond to her former beau and the three discussed work.

But there was more to it than that. Edmund and Rosemary’s feelings were still strong, and when Raymond was out of town for a couple of nights, Edmund and Rosemary dined at a Hungarian restaurant and “almost certainly spent the night together”.

And as well as an insight into the personal, the book reveals much about the expectations and restrictions women faced through the 20th century. Rosemary’s gender impacted on her opportunities, how she was treated, expectations and a never-ending number of other ways.

As well as tracking how their parents’ orbits intertwined at times, they have built up a more complete picture of Rosemary’s life.

In 1956, Rosemary planned to go into social work and started at the London County Council. It was here she met Helen Stocks – and the pair spent time together in Rosemary’s Dorset cottage.

“For a year, Rosemary was dizzyingly happy,” the book states.

The affair ended in 1961 and at the same time Rosemary noted that Raymond’s lover, an anthropologist, had left England.

“I have told you and I have told my mistress this: that you come first in my life,” Raymond tells his wife.

“If you want me to give her up then I suppose you have the right to ask, but I won’t be lectured about fidelity.”

This same-sex relationship was another surprise.

“This was more amazing to me,” says Hugh. “Helen introduced me to fish and chips out of paper. That was definitely not my parents’ style.

“This dashing, vivacious young woman came into our lives and she was lovely.”

In the immediate post-war period, Rosemary became friends with Betty Belshaw, married to anthropologist Cyril Belshaw. Betty appears regularly in the letters and diaries – and in 1978, was the victim of an unimaginable tragedy.

Betty disappeared in 1978 and her husband was charged with her murder the following year.

We are shown the impact this awful situation had on the couple.

While Rosemary had compelled her story to be heard by the fact she wrote it down does not mean publication was straightforward for Hugh.

“My mother would have been terrified and anxious,” he believes.

“But part of her would be proud that her writing was important enough.”

For Loulou, this element – of revealing a personal life of a parent without their permission – has been conflicting.

Her relationship with her father was part-bounded by conventions outside their control.

She believes Rosemary’s story is valuable and deserves to be shared, but that her father would not agree.

“He was a private man concerned with his reputation,” she says. “He would not want criticisms made public. He would have found it embarrassing.

“However, I think Rosemary had an eye on posterity, as well as being motivated to write to offload her thoughts.”

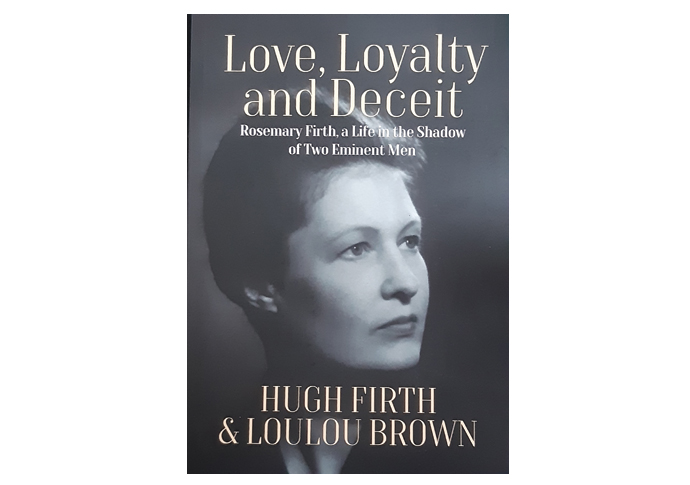

• Love, Loyalty and Deceit: Rosemary Firth, a Life in the Shadow of Two Eminent Men. By Hugh Firth and Loulou Brown. Berghahn Books, £19.95