Review: Hawkers and the History of London by Charlie Taverner

A new book tells how street food in the capital goes a lot further back than the trendy stalls we see nowadays

Thursday, 6th April 2023 — By Peter Gruner

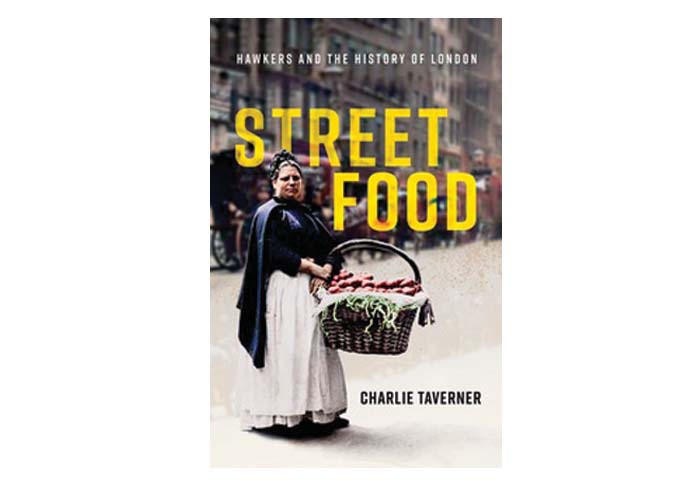

A shellfish stall, just one example of the type of street food featured in the book by Charlie Taverner [LSE library]

A HIGHBURY writer, whose book about the history of the capital’s street food has won rave reviews, was inspired by his favourite markets in Islington and Camden.

In Street Food: Hawkers and the History of London, Charlie Taverner traces traders over three centuries, from those selling essentials like vegetables, fish, fruit and milk for the poor right up to today where stalls can purvey “posh nosh” from all parts of the world for foodies.

Talking to Review, he said that today many markets were doing better than ever due to tough financial times and the need for people to shop cheaply.

Taverner, who studied the subject at Birkbeck university in Bloomsbury, is also a great a fan of Arsenal, living not far from the Emirates Stadium, but not because of the football. “I like match days but I don’t attend matches,” he said. “It’s the noise outside the ground and the fantastic atmosphere I like. There are stalls set up in people’s gardens which remind me of the older street markets.”

Among his favourite local markets are Ridley Road, Dalston, and Chapel Street at the Angel where traders have provided food for more than 150 years.

“You can buy almost anything at Chapel Market,” he said, “from clothes to greeting cards, fresh fish and fruit and vegetables. And with a Farmers’ Market, selling fresh produce from small farms, which was introduced 10 years ago, you have the old and the new systems.”

He also visits Camden Markets, where he describes an amazing range and diversity of food.

Camden today is home to at least 19 regular markets, eight of which are managed by the council. The others are privately run.

The book suggests that street trading is often tough, poorly paid, and insecure work that few would rush to do. But Charlie maintains that city life would have been lost without it.

He writes: “We must remember that markets produce an important means of work and earn money for those struggling to survive including immigrants.”

Charlie Taverner

Poor Italians who arrived in London in the 19th century congregated north of Holborn in the courts and alleys around Hatton Garden and Saffron Hill. Many subsisted by making and selling ice cream. The 1881 census counted 46 ice cream vendors across London, all but one born in Italy, all but a handful living close together in Clerkenwell.

Britain’s first ever Mule and Donkey Show was held in 1864 to highlight and reduce the abuse of animals by street traders. There were many incidents where the animals just couldn’t carry heavy loads. The event was held at the Agricultural Hall, a site today occupied by the Business Design Centre at Upper Street, Islington.

Taking part were several classes of animals, with those owned by hawkers shown alongside an Egyptian breed belonging to royalty. The middle of the hall was boarded off for racing, with costermonger jockeys racing five times around a track.

Much of the fruit eaten in early Tudor London was imported from the Low Countries and France, but from the mid-16th century home production increased in scale. Pioneering growers planted orchards in the counties that ringed the capital, employing varieties and know-how from the continent.

Kent quickly secured the first place. From the fruit belt nestled between the North Downs and the coast, Kentish apples and cherries were carted or shipped the short journey to the metropolis.

King’s Cross was famous as a potato depot where wagons of spuds rolled in from the east and north of England. St Pancras had a dairy of 69 cows and a bull, along with 16 horses, 120 loads of hay, grain carts, milking tubs, and pails.

Covent Garden gained an impressive market hall enclosed in glass and iron, but was still mocked in Punch throughout the 1880s as “Mud Salad Market”, due to its messy passageways, congestion in the nearby streets, and shoddy management.

Dickens described Covent Garden and its environs, where “men are shouting, carts backing, horses neighing, boys fighting, basket-women talking, piemen expatiating on the excellence of their pastry, and donkeys braying”.

In 2018, the UK’s street food industry was worth £1.2 billion and supposedly growing faster than all sales of fast food. In recent years street food markets have sprung up across the City in empty car parks, pedestrianised streets, and buildings awaiting development.

The new cuisine is drawn from across the world: gourmet burgers and slow-cooked meats from the United States; tacos, ceviche and empanadas (savoury pastries) from Latin America; noodles and dumplings from China; steaming broths from southeast Asia; and street snacks from India that broke the mould of the Brick Lane curry house.

Vending unfit food was one of the common reasons for which street sellers were brought before the police courts. In 1897, Islington’s sanitary inspector charged an Essex Road hawker, John Hurley, with selling bad quality pears and greengages. He was fined £5.53.

Street sellers were believed to cover up flaws with deception. Costermongers tried boiling oranges to make them puff up, mingling cherries of variable quality, and stuffing the bottom half of containers with detritus such as cabbage leaves. One man selling grapes in Camden

Town set his scales on an incline, so that every pound of fruit weighed an ounce and a half less than he claimed.

• Street Food: Hawkers and the History of London. By Charlie Taverner, Oxford University Press, £30