Life of Michael

‘What we were doing was producing non-conformity.’ Python Michael Palin, 73, shares with Julie Tomlin his concerns about the current generation of creatives

Monday, 30th January 2017 — By Julie Tomlin

Michael Palin at home in Gospel Oak

He was one of the six-strong team behind Monty Python, the surreal comedy group that is still considered a benchmark for alternative humour. Ask him why he thinks his generation made so many waves – not only culturally, but socially and politically – Michael Palin says “luck” played a big part.

“We were very fortunate, because we happened to be there at that particular time when any idea could be tried out, and we were in the vanguard of such an energetic, creative period in art, music and fashion,” says 73-year-old Palin, who lives in Gospel Oak.

Post-war Britain was a “fairly conservative” place where the “old values” still held sway and the Establishment was “very much in control” says Palin, who first sensed “something in the air” when he arrived at Oxford University to read history in 1962.

“There was very little money around, we were pretty much on our knees economically, very much dependent on America to keep us going, and then suddenly there was a bit more money, there was more economic confidence and this had to lead somewhere,” he says. “People had to question all the old values which were there and which my parents represented.”

This questioning set him and his contemporaries apart from their parents, many of whom had experienced two world wars and a Great Depression.

“They didn’t want to rock the boat anymore. It was all just hang on, let’s just take a deep breath and not do anything silly,” says Palin, who was born in Broomhill in Sheffield.

Comedians like Peter Cook and Dudley Moore, as well America’s Tom Lehrer, who sent up authority figures and probed subjects previously deemed “untouchable”, had a big impact on him, he says.

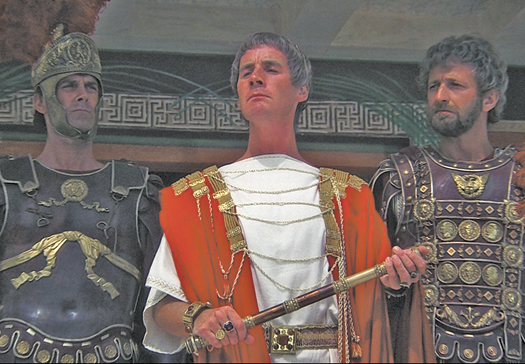

Michael Palin with Graham Chapman, right, and John Cleese in the film Life of Brian

“The other big thing, for me was the success of the Beatles, because before that we had crooners, and nice American jolly pop songs, which I liked, but this was something more powerful,” he adds. “And, of course, plays and films were changing, there was Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, these northern writers like Sillitoe and actors like Albert Finney coming out and providing you with something you had never really seen before, it was all quite a shock to the system.”

After graduating in 1965, Palin became a presenter on a comedy show called Now! along with Terry Jones, who remains a close friend. Both then joined The Frost Report, where they worked with a host of talented comedy writers, including future Python members John Cleese, Graham Chapman and Eric Idle. First aired in 1966, The Frost Report was very different to anything that had been done before, says Palin.

“It was actually making comedy about serious things,” he adds. “We found ourselves in among all these writers, writing this new television programme, and listening to new music, seeing new fashion from people like Mary Quant and a whole new confidence that burned for about two or three years.”

It was during their time on The Frost Report that the would-be Python team not only refined their writing skills but began discussing ideas for a new show.

“All we wanted to do was to write a show that would make people laugh a lot, without any producer from the BBC giving us a template or anything like that,” says Palin. “We all felt that there were certain limitations and restrictions, and wouldn’t it be wonderful if you could just write a purely silly TV comedy show.”

Monty Python’s Flying Circus was first broadcast on the BBC in October 1969 with its now iconic animation by Terry Gilliam, who was part of the team. Much of the show’s success was due to the BBC’s hands-off approach at the time, says Palin: “We were very fortunate because the BBC could just make a small show like that, put it out late at night and say that’s it, get on with it,” he adds. “Nowadays you would have to give a much more careful presentation of what you wanted, there would be much more scrutiny of how the programme was going to be set up, how it was going to be done, and by that time you would have killed it off.”

Palin’s first novel, Hemingway’s Chair, examines the impact of “the men in suits” on a small-town community, and he remains concerned about the impact of “high-tech” management on not only creativity, but on every aspect of people’s lives.

“I am worried that it’s become a deadening factor which is really there to make sure people are kept in their place,” says Palin who admits to some nostalgia for “the chaotic mess of the 60s” and the “pretty awful” management of the 70s. “Somehow there was much more opportunity to be spontaneous, a chance to be experimental, and you didn’t have to have it immediately quantified, commercialised and tied up and marketed,” he says.

‘I’m 73 and I’m still doing stuff, and I’ve not noticed the years pass at all,’ says Palin, pictured with Julie Tomlin

Palin went on to make several successful films with the Python team and then Ripping Yarns with Terry Jones before launching himself as a travel writer and broadcaster in the late 1980s with the TV series Around the World in 80 Days. He continues to make documentaries, has published his diaries, which he’s kept since 1969, and has written four novels as well as children’s books.

Friendships, rather than any big plan, have played an important role in shaping what he does, says Palin, adding that relationships on social media can’t generate the same creative spark.

“I like to think I can plan it out, but it’s never like that. Even now, if a friend says let’s have lunch, then I do that,” says Palin, who says his concern about social media is that it can’t generate the same creative spark. “Having friends and working with them has always been important, seeing what comes up. That’s something my parents didn’t have, those kind of friendships, or the freedom we had. That’s an important part of creativity.”

As well as setting greater store by friendship than his parents, Palin says that, along with many of his generation, he has a very different relationship with his three grown-up children, compared to the one he had with his parents: “We didn’t share a great deal,” he says. “Socially they did their thing and we did our thing. I feel, I hope, that my children are much closer to me.”

Being part of a “stroppy generation that has produced a wonderful amount of grumpy old men and women,” he has also taken a very different approach to ageing compared to that of his parents.

“I’m 73 and I’m doing stuff still, and I’ve not noticed the years pass at all,” he says. “My Dad was just waiting for 65 to come along when he could give up this boring job and move home and go and live by the sea. I’m still looking around for work, worrying about the day when I’ve not got anything to do.”

He’s keen to avoid becoming an “old fart” who is an “obstacle to younger people doing what they do” but he’s also enjoying popularity among younger people who watch Monty Python on YouTube. Named alongside Cleese and Idle as one of the country’s top 50 greatest comedians, Palin is less concerned about being a “has been” than he is that younger generations aren’t pushing boundaries in the same way as his did.

“I walk around London and it’s so much more enjoyable than it was when I was growing up in terms of what’s happening on the street, but I just look at people coming up and I sometimes think they’re all doing the same thing, they’ve sort of achieved and lived what we were struggling to do at the time, and there isn’t so much struggle now. I think it’s in danger of producing a conformity in creativity, whereas what we were doing was producing non-conformity.”

And so, what he hopes for is not dissimilar to his ambition as a youthful writer: to instil a little silliness in the world.

“Silliness is something that people can’t quantify, can’t tidy up, can’t sell. I think that’s important.”