Loss adjustment…

Peter Gruner talks to Cosmo Landesman about his latest book, in which he writes about his son Jack, who took his own life

Thursday, 20th October 2022 — By Peter Gruner

Cosmo Landesman

ISLINGTON writer-journalist Cosmo Landesman, whose son took his own life, has told Review that mental health care in Britain is still very much a “Cinderella” service.

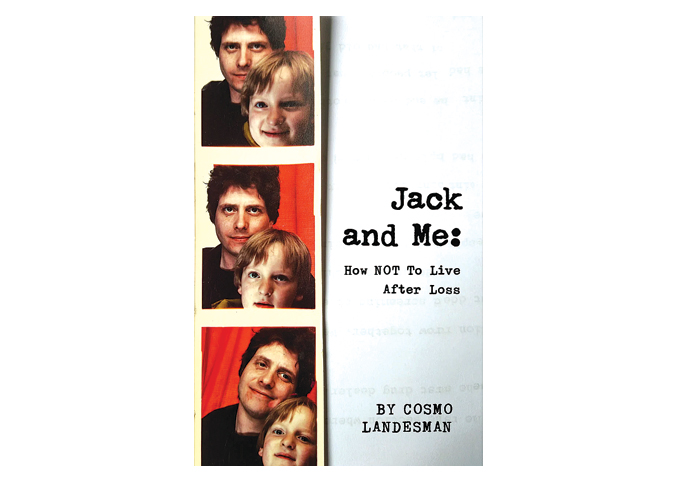

In his often angry, humorous and edgy new book, Jack and Me: How Not To Live After Loss, Cosmo, who lives off Essex Road, describes the enormous stress, pain, and guilt he suffered after the tragedy.

Jack, Cosmo’s son with his former wife, writer Julie Burchill, died in 2015, aged 29, following years of heavy drug use and regular low moods.

The couple divorced when Jack was 10 but he lived with each of them at different times and was regularly in touch.

Though he was bright, sensitive and cheerful as a youngster, who learned to play the guitar and joined a number of bands, things began to get emotionally difficult for him in his teens and 20s.

He liked to stay with his celebrated American-born grandparents on Cosmo’s side, Fran and Jay Landesman, at the Angel. They both died in 2011 four years before Jack’s untimely demise. Fran, 83, was a singer and poet, and described as the “godmother of hip” while her “Bohemian” husband, writer and publisher Jay, died aged 91.

Cosmo illustrates in grim detail what it was like having a loving son who had a tendency to self-harm and who occasionally admitted to his father that he no longer wanted to live.

A writer for the Sunday Times and The Spectator, Cosmo said: “Mental health is still very much a second-class concern after cancer and bodily health. We talk a lot about the importance of mental health but the actual infrastructure to deal with the problem is not available.”

He writes that for a long time he “ducked the issues of suicide and mental health”. But he has “worked on his own anger” and taken up meditation, something his late mother Fran first introduced him to as a child. He, like her, has now, he says, adopted a semi-Buddhist approach to life.

Cosmo still has happy memories of his son visiting places like Essex Road library, Camden Passage antique market and Jack’s beloved Camden Town.

What was Jack like? Cosmo writes that often the “Jacks of this world are lost, lonely, depressed, often on drugs and off the grid of adulthood. They are full of hurt and anger and self-hatred.”

But Jack also had a gentle and good-humoured side. A former girlfriend who he met in Camden Town described him as “funny and different from other boys”, in that he was not interested in how she looked or out to make a sexual conquest.

His worried mother Julie Burchill, who lives in Brighton, told him: “You’re very clever and you have to stop looking on the dark side. Volunteer for a charity and you’ll meet people that way. Go back to university. My friend got her degree at 50.”

He could also be the young man who approached you on the street, Cosmo writes, and asked for spare change for a bus or a hostel. “In my mind I see Jack and he’s always alone, pacing back and forth in the open cage of his solitude.

“We don’t teach our young how to deal with loneliness, because we don’t know how to deal with it ourselves.”

At 18 Jack did reasonably well at school and got a place at Queen Mary University of London to read English Literature. He didn’t finish the course. He suffered from occasional anxiety and depression but, as Cosmo writes, who doesn’t at that age? However, Cosmo was convinced that Jack had been hiding a drug problem from him and Julie. He was also occasionally self-harming.

“We modern dads like to think we can read signs of unhappiness. But certain kids are good at hiding their problems and pain,” he writes.

In his early 20s Jack became a patient at the private Priory clinic, where he was formally diagnosed as depressed and at risk of self-harm. He was given anti-depressants and became an outpatient. He found the therapy helpful and mum and dad were relieved.

However, at 24 he was soon drifting in and out of low-paid jobs and rock bands.

When he moved in with grandparents, he refused to use a proper room. Instead he insisted on camping in the toilet on the first floor of their spacious home in Duncan Terrace.

Cosmo was appalled by these living arrangements, but his father Jay was more philosophical.

Jay told Cosmo: “‘Don’t be so bourgeois! Let the kid do his own thing. If he’s happy living in a toilet that’s fine. If not, he’ll figure something out. He’s a smart kid.’”

Soon Jack was under the care of social workers from the Camden and Islington Mental Health Assessment and Advice teams, who were warning him about how drugs were affecting his life.

Cosmo writes about his different emotions while carrying his son’s ashes along Islington High Street. It’s a moment of huge sadness but Cosmo can’t help imagining the humour. “What if I took a tumble and out spilled Jack.”

Writing the book, Cosmo said, was a reminder of his son’s voice, music and even smell. “There was his mad infuriating Jackness and the grief and guilt it provokes in me.”

Finally Cosmo urges people to “be kind” to each other. He quotes Aldous Huxley who was embarrassed that after a lifetime of trying to understand the human condition the only advice this very clever man could offer was, “try to be a little kinder”.

• Jack and Me: How Not to Live After Loss. By Cosmo Landesman, Black Spring, £20