Mission to find missing Somers Town finials leads to auction find in United States

Historians search for stolen decorations

Friday, 10th February 2023 — By Dan Carrier

Finials which once decorated courtyard in Camden

DID they come in the dead of night, armed with crow-bars and torches? Or were the thieves dressed as workmen, carrying ladders, whistling nonchalantly, hiding in plain sight?

However the grand Somers Town art theft took place, the outcome was a scandalous piece of destruction. In the courtyards of the historic St Pancras Housing Association estates, decorative sculptures – known as finials – were designed by the renowned artist Gilbert Bayes to sit on top of washing lines.

He also produced friezes and other facade decorations in a period of intensive work in the 1930s.

But these remarkable pieces – of which there were over 100 – have all but disappeared, stolen from their perches over the years.

This week, two of the finials were back in Somers Town after The Somers Town People’s Museum – known as A Space For Us, and based in Phoenix Road – raised thousands of pounds to bid for a pair at an auction in Florida. The campaign to recover the finials has been spearheaded by the museum’s Diana Foster and social historian Stephen McCarthy – and while they are thrilled to have recovered two, they know there are scores still out there.

Appealing for help in bringing the set back to Camden, Ms Foster said: “We hope someone will have one under their bed, or in a shed, and are not quite sure what to do with it.”

Currently, some washing poles are decked with fibreglass copies. The recovered finials will be on display but will have to stay under lock and key. Installed between 1931 and 1938, Bayes drew on fairy tales from Hans Christian Andersen and the Brothers Grimm.

Stephen McCarthy and Diana Foster on the trail of the missing finials

Other courtyards had a focus on nursery rhymes, while in Chalton Street, a statue of St Anthony overlooks the St Anthony’s flats courtyard. The saint once gazed over a circle of washing posts topped by finials with a fish motif.

Other religious themes included St Martin, surrounded by 12 galleon ships; St Joseph, represented by woodworking tools; and doves for St Anne.

They were more than a quirky piece of architecture – they were striking examples of a belief that public art had a key role to play in improving people’s environment and living conditions.

Mr McCarthy said how he first spotted the decorations, which once could be found on estates in Sidney Street, Eversholt Street, Drummond Street, Athlone Street and in York Rise, Kentish Town.

He first noted the art while delivering leaflets for the Somers Town Community Association.

“I was taking leaflets round the estates and it was quite a boring job, but made all the better for seeing this artwork around. There was a real sense of joy in the creation of these working-class estates. “I noticed art was going missing and I was outraged by it,” added Mr McCarthy.

The thieves have never been caught – and the police told the group they were unable to investigate as no one could provide an exact date they started disappearing. Despite the fact they are showing up regularly at auctions, and were clearly removed without the owners’ permission, no criminal investigation has ever been launched.

Ms Foster first began looking into the issue after reading an article in the New Journal in 2016, which highlighted the fact so many had been stolen.

She said: “I was intrigued by the idea that the St Pancras Housing Association wanted to make their homes beautiful. Why shouldn’t working-class people have public art? It was scandalous that they were disappearing and so many were lost, stolen or broken.”

The bird finials in their rightful home

After it became increasingly clear the finials were being targeted, the St Pancras Housing Association – now called Origin Housing – took the decision it would be safer to remove the remaining 100 and put them in storage while they worked out how they could be kept on display securely.

But disaster struck: after they had been removed from where they were stored, the entire collection disappeared. And over the years, they have begun to turn up at auctions around the world, going for anything above £6,000 a time.

“The ones left in place now are copies made from fibreglass,” says Ms Foster.

“It appears someone noticed where they were stored, knew they were valuable and took them away. “Our question is: Where are they all now?”

Leads have been few. One tenant saw some being loaded into a van – but it’s not clear if this was when the housing association removed them. Attempts to find out about the provenance of those offered for sale have also drawn a blank, with auction houses unwilling to co-operate, offer evidence as to where they came from or encourage police officers to run checks.

“We wonder if someone, somewhere, is sitting on them and releasing them slowly to try not to attract attention,” says Ms Foster.

Both Bonhams and Christie’s show examples of Bayes’ finials on their websites. It is not stated where they have come from or if they are his Somers Town work. Christie’s identify at least 14 Bayes finials sold, while Bonhams records details of a sale in 2014 that reached a price of more than £13,000.

Ms Foster has kept a careful eye for any possible leads and has contacted numerous art sales when a Bayes finial comes up.

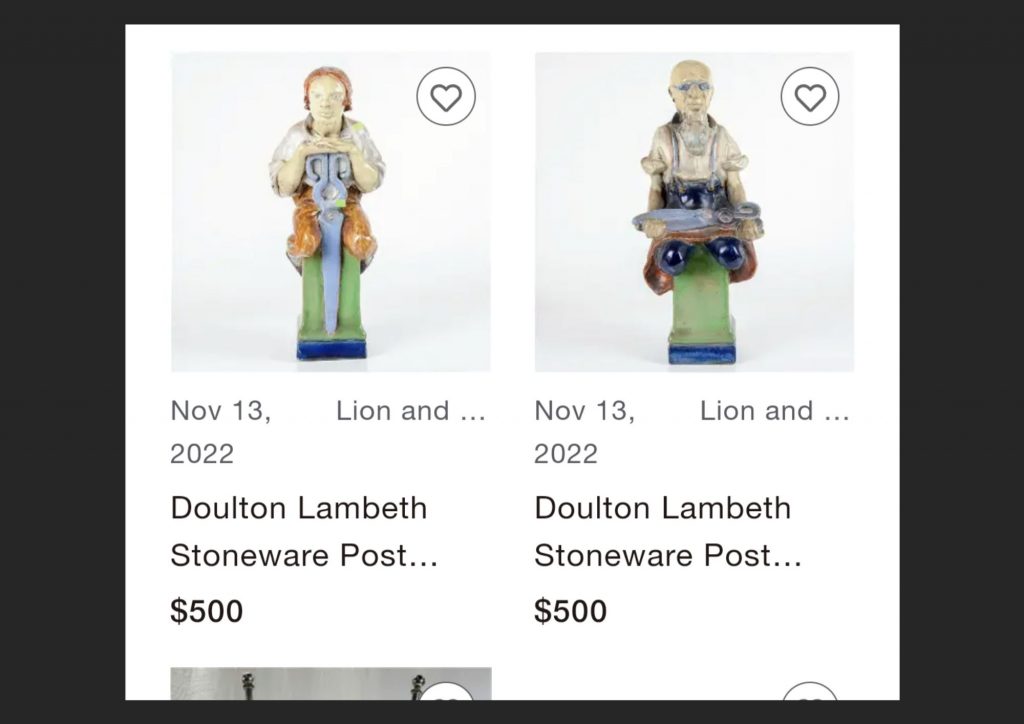

Then, last autumn, she noted a pair of finials were offered for sale in Florida. The asking price for the pair, which depicted tailors at work, was £6,000 each. Ms Foster and Mr McCarthy called the dealer and asked him if he knew their provenance.

“He said: ‘I can assure you I got them from someone who has worked with me for 20 years’, but he refused to give me their name,” said Ms Foster. “These were a pair that had been stolen, taken without any protest. I thought that’s it, I’m going to raise the money and buy them. I thought they could be the only ones to come up for years and years.”

Auction listings for the finials

Ms Foster now had a week to raise funds so she could bid for them – and remarkably managed to get £13,000 together in time for the sale by approaching the Bayes Trust, Origin Housing and other grant-givers. “It was exciting – but daunting,” she admits.

From her sitting room in Levita House, Somers Town, she and friends gathered round a telephone patched through to a bidder in Florida. They waited anxiously as the lots came up – and then set out to bring two of the many missing pieces back home.

“It was nerve- wracking,” she said.

They had a tough decision to make – what if one went over £6,000? Should they risk draining their fund for just one?

Ms Foster said: “The bidding began, for a figure of a tailor, and I came in when it reached the £5,000 mark. I was prompted to bid by the auctioneer – and then the hammer came down and I was told I’d got the first.” The second, of a draper, was also secured. Then came the anxious wait for the works to be delivered.

“A month or so later a massive, heavy box arrived,” recalls Ms Foster. “We opened it up – and seeing them in the flesh, seeing the detail – it was a good moment.”

The Little Mermaid, an example of Bayes’ public art

Their importance to Somers Town and public art should not be underestimated, the pair add.

“If I went to Piccadilly Circus and removed Eros, and then sold it somewhere, how would Westminster Council feel? “How would people react if Eros was sold privately at an auction in Florida?” With so many more to be recovered, the museum and Origin Housing will be keeping their eyes on auctions around the world.

Ms Foster said: “We want to bring as many as we can back home to their rightful place in Somers Town, where they belong.”

The People’s Museum: A Space for Us, https://aspaceforus.club

Sculptor who believed in art for everyone

IT was not solely about producing the finest, most eye-pleasing and delicate works his talent could muster – for sculptor Gilbert Bayes it was about who could see the triumphs of his studio. Private commissions might pay bills, but Bayes saw beyond patronage.

He believed art was crucial to elevating the human experience, for building better societies, creating civic pride and diluting the scourge of the post-Victorian city slums that so many were condemned to live in. Gilbert was born in north London in 1872, the son of artist Alfred Bayes.

In childhood he decided he wanted to be a sculptor, and by 17 had work accepted at the Royal Academy. He settled in Swiss Cottage in 1906 with his wife, fellow art student Gertrude Smith.

Gilbert’s stock was on the rise: he was commissioned in 1911 to design the Great Seal for George V, taught at Camberwell School of Art and was exempted from serving in the war on medical grounds and then, because of his contribution to war memorials, created while the conflict raged. After the carnage of the First World War, he earned further commissions for memorials all over the Commonwealth.

Gilbert Bayes modelling the dragon finial for the St Pancras Housing Association in 1937

But Gilbert found the work taxing, a reminder of the monstrous inhumanity that had murdered a generation. He wanted to bring joy as well as solace through art – and with his Arts and Crafts ethos, he wanted to bring the beauty his talent could create to as many people as possible with no scrimping on quality.

It meant, when he was approached in the early 1930s by the St Pancras Housing Association to beautify the estates Father Basil Jellicoe was building to replace the decaying slums of the area, he was inspired.

A Christian Socialist – very much like the St Pancras Housing Association founder Jellicoe – he also bought shares in the association to help pay for the new housing he was commissioned to decorate. Bayes came from the Arts and Crafts school, made popular by William Morris.

It celebrated craftsmanship, saw beauty in the making, and believed that no one should be cut off from the aesthetic pleasures of human reason by their economic status.

This was a crucial element to his enthusiasm for creating the art. For Somers Town, Bayes made relief models of fairytale characters for the housing association’s school.

He cast beautiful figures at the Doulton pottery in Stoke on Trent. In 1929 the family moved to Greville Place in south Kilburn, a house that had enough space for two art studios and a large garden for Gilbert to put in situ some of his works. It was from here the finials took shape.

Other commissions further reveal his love of public space to display his talents.

They include designs for Selfridges in Oxford Street, with the “Queen of Time” clock that is above its main entrance, a panel in bronze of Pegasus for the foyer, and a Madonna and child for the roof. Friezes were made for Lord’s cricket ground, the Saville Theatre and the BBC Concert Hall.

Today, his work graces the V&A where a gallery is named after him, and his entire range of work in numerous mediums is highly sought after in public and private collections around the world.

Proud to be part of the story

By Carol Carter, chief executive of Origin Housing

ORIGIN is a locally-based housing association, founded in Somers Town as St Pancras Home Improvement Society almost 100 years ago with a mission to provide decent, affordable homes and support for individuals and communities to flourish.

We are therefore delighted to have been able to contribute to helping recover these lost local artefacts. Created and produced by renowned sculptor Gilbert Bayes, the finials are part of the unique history of the Somers Town community and the lives of working people, and represent the belief that working-class communities should have access to the inspiration of art in their everyday lives.

We are grateful for the hard work and passion of our valued partners, A Space for Us, in bringing Gilbert Bayes’ artworks back to our community and helping to restore a sense of pride and place for local people.