‘Music is political’

Dan Carrier talks musical influences – and Kentish Town – with Eddy Grant ahead of his appearance at the British Library

Thursday, 18th April — By Dan Carrier

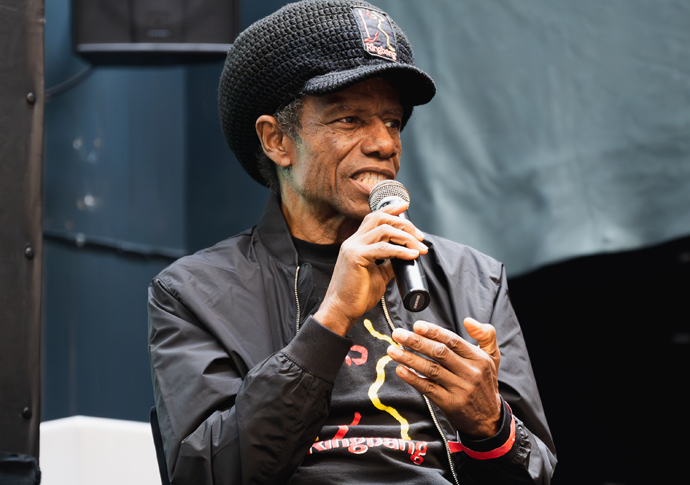

Eddy Grant: ‘By being educated in music it comes to a point where I knew I did not have to believe any nonsense I was being taught’

FROM working in what was seen as the first multi-racial band to hit the big time to creating a unique fusion sound of his own, musician Eddy Grant has spent a lifetime pushing against man-made boundaries and fighting ingrained prejudices, from race to how to produce music.

Eddy, who grew up in Kentish Town and now lives in Barbados, is giving a lecture in two weeks at the British Library as part of a new exhibition series called Beyond The Bassline: 500 Years of Black British Music. He opens the show on April 26, while other guest speakers include Joan Armatrading.

And at the same time, he is re-releasing a re-mastered version of his seminal 1982 album, Killer on the Rampage, an LP that brought him world-wide accolades.

It was his sixth studio album and seminal singles Electric Avenue, War Party and I Don’t Want To Dance came from the LP.

The album was special to Eddy as it represented a new beginning.

He had left England to move to the Caribbean and had begun building a studio of his own in Barbados. Killer On The Rampage was the product of this period.

But he had to overcome an immediate problem when he arrived. He had packed up his entire London life and sent it with him – but everything went missing.

“The album that should have been made was never made – because British Airways lost all my luggage, everything. I arrived in the clothes I was wearing. I even lost my toothbrush. I just had a T-shirt.

“It was a new start – my whole life was about to change.

“And I’m not complaining – it actually did a lot of good for me. I had to start writing all over again,” he recalls.

The singer looks back over 40 years to recall the creative sense he experienced as he penned such tunes as Electric Avenue.

“I have to go deep into my memory to feel what it meant to me,” he says. “I used what was around me, and enjoyed the effect the surroundings were having on the whole creative process.

“I was living a very spartan life, having come from London. I was now in a hammock by the ocean and that certainly influenced some of the sounds on the album, like Culture Revolution.”

The brilliant political reggae tune War Party, which is as relevant today as it was then, reflected his sense of current politics and world history.

“Music is political, because of its expression and communication and how we relate to each other,” he says.

The oppressive history of Caribbean islands was also unavoidable.

“I could look at the Atlantic from a hammock, and then go to the plantation where I was building a house and studio, and here I was going to work and live, and I could look out at the cane fields. That also gave me inspiration,” he adds.

Eddy moved to Kentish Town in 1960 aged 12 and attended Acland Burghley school.

“It was a fantastic time, looking back,” he says.

“I fought on a daily basis to retain the dignity that made me me. It was so very different to what I had experienced in Guyana. I had people coming down on me, telling me who I was, what my place in society was, if there was a place for me at all.

“It’s like being thrown into a deep well and you have to drag yourself out. I found dignity in my work, dignity in creating music.”

From London to the Caribbean, Eddy saw how history is told by the so-called “winners”.

“I have lived in two great areas of the world,” he observes. “The Caribbean has made a tremendous impact. I recognise its value intellectually.”

But the taught narrative is of the superiority of Western thought, to the detriment of other human endeavour that is just as relevant, important and rich, he adds. Eddy has become a music historian, collecting and archiving thousands of calypso songs and other forms of expression from the islands’ past.

“People in the first world, for want of a better way of phrasing it, recognise their intellectual values. Our education has told us we can only accept others’ intellectual values. I have grown up in a world where people who have made music in the first world have been told their music is more important than anyone else’s. It is strange to live in a society that seems to dismiss the intellectual property of my history and background.”

He looks back at the album that cemented his place as a global star with affection.

“It is interesting to hear today and it has given me a reason to go back to the beginning of my career as a solo artist, and go back and remember The Equals.

“I look back and I am proud of what I’ve done. It has brought me a lot of joy. I have worked hard all my life to make music the best I can and in my own way.”

Eddy has dedicated years to conserving the calypso tradition, saving old recordings, making new ones, writing down what were often spur-of-the-moment lyrics created for a Saturday night dance. He has become a leading proponent of Caribbean music heritage.

“It is only natural to be into calypso,” he adds. “I recognise its value. The Caribbean and its cultures have often been subsumed by others. My mentor, Roaring Lion, the oldest living calypsonian, pointed out to me that by virtue of the closeness of the French who enslaved Africans we took on a lot of what they considered was their culture. We mimicked them, and the British influence was pronounced too.

“It meant the drums of Africa were subsumed by the instrumentation of Europe and lead to a period where the drum was not recognised – which is wrong for many reasons, one of which being that every instrument is a drum of some form. We were conned into believing our music and instruments had no value.

“I have grown up surrounded by prejudices of this type. By being educated in music it comes to a point where I knew I did not have to believe any nonsense I was being taught.”

The outward-looking approach to sound means Eddy has never been hidebound by genre or tradition, and as a multi-instrumentalist, has been able to find the way to express what he can hear internally.

“Everything I have ever heard shapes me as a composer,” he adds. “I have had so many great mentors – from the Mighty Sparrow to Howlin Wolf and Muddy Waters, to Miles Davis and John Coltrane… I have been to all the junctions where music meets. If you hear something you like you think, I can play that, I can use that… But I am not Vladimir Ashkenazy – I am Eddy Grant and I have to find what constitutes being Eddy Grant. That is what I play.”

His hit I Don’t Want To Dance could be considered a mixture of reggae, disco and funk. Not so obvious is the influence of calypso on the song. Eddy wrote it, it was once said, as a farewell letter to England as he left the country to the backdrop of the aftermath of the Brixton riots, Thatcher, youth unemployment and ingrained racism. The storytelling element is important.

“I wrote it as a calypsonian,” he says. “Calypso is about expression and communication and how you interpret the words. I Don’t Want to Dance is a double entendre – it’s up to you how you consider it. That’s calypso.”

• Join Eddy at the British Library to launch the Beyond The Bassline season. The evening will be a retrospective conversation with Colleen “Cosmo” Murphy about his career. Friday, April 26, 7pm. https://beyondthebasslineevents.seetickets.com/search/all