Power couple

Peter Gruner talks to historian Jenny Uglow about her new book, which tells the scandalous tale of ’Appy ’Ampstead artist Cyril Power’s relationship with Sybil Andrews

Thursday, 6th October 2022 — By Peter Gruner

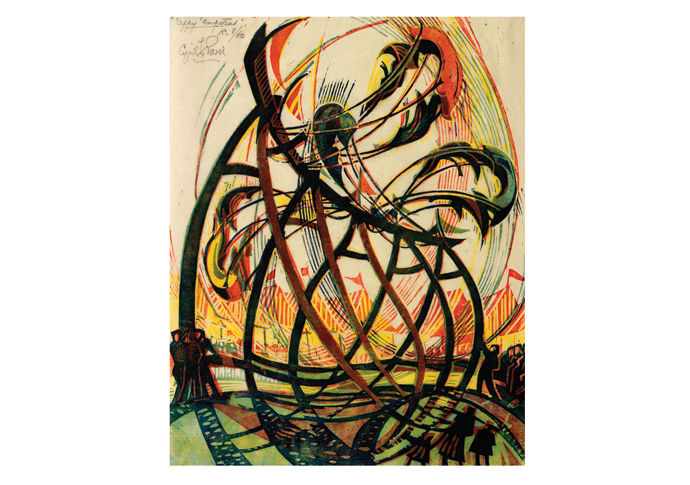

Cyril Power: ‘Appy ‘Ampstead. Courtesy of Osborne Samuel Gallery and the Estate of Cyril Power

’APPY ’Ampstead was artist Cyril Power’s abstract celebration of a Hampstead fairground, a print that became popular not long after the death and devastation of the First World War.

He also created linoprints of overcrowded tube stations and trains, such as scenes at Tottenham Court Road station.

Not everyone was aware, however, or would have approved, of the fact that Cyril had originally left his wife, Dolly, and four kids back in Suffolk to run off to north London with aspiring painter Sybil Andrews, who was 26 years his junior.

The odd couple first met in Bury St Edmunds, where they both lived in the early 1920s, and soon were painting watercolours together. When Sybil, 24, moved to rooms in Bernard Street near London’s Russell Square, Cyril, nearly 50, an architect by profession, abandoned his family and joined her.

Historian Jenny Uglow’s fascinating new book, Sybil and Cyril Cutting Through Time, explores Power’s work in collaboration with Sybil.

Uglow describes how Cyril’s wife Dolly was philosophical and kept feelings to herself, but his leaving was extremely tough on the family, particularly financially.

She writes that the First World War may have affected Cyril’s attitudes. “His infatuation was a post-war crisis as much as a mid-life crisis. Mass death in the trenches had made life seem so short that many men and women felt it was imperative – almost a duty – to live true to one’s deep desires and talents, to escape the ruts.”

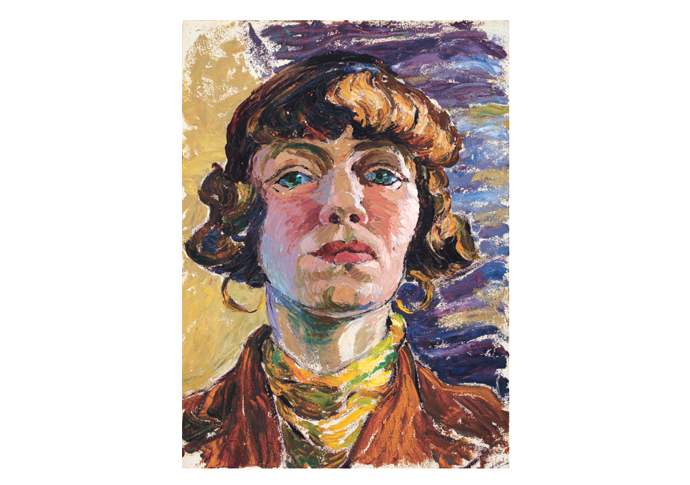

Sybil Andrews: Self-portrait, c1938. copyright Glenbow Museum, Calgary

Sybil and Cyril worked together in the capital for 20 years and as well as their private art work, earned money from London Transport by designing sports and entertainment posters under the name Andrew Power.

Uglow is a great fan of the couple’s popular linoprints. Speaking to Review, she said: “I like so many of them, but I’m particularly moved by Cyril’s prints of the Underground, such as Whence and Whither, with all the people flooding down the escalator, and Sybil’s country prints, like the great horses coming over the hill in Tillers of the Soil.”

Cyril’s1933 Hampstead fairground illustration, ’Appy ’Ampstead, described as like an upside down spinning top, was inspired by a comic music hall song of the time by cockney singer Albert Chevalier.

“The toffs may talk of Rotting Row, / There ain’t no place on earth / Like ’Ampstead, ’appy’ Ampstead for / To get yer money’s worth / The bloke as owns the cocoa-nuts / ’Twon’t break yer to support, /Three shies a penny’s wot I calls / A find old English sport! / Oh, ’Ampstead!”/

Sybil and Cyril may not have endeared themselves to many local artists of the time. Uglow writes that they rejected the “progressive” mode of Walter Sickert and the pre-war local Camden Town Group, as “an artificial, false and aggressive imitation Bohemianism” with its scenes of “unfinished meals, uncooked edibles, compositions of sordid intimacies [sic] emanating from back bedrooms of Camden Town attics.” With equal ferocity, they damned the “self-sufficient smugness” of Victorian narrative paintings and still lives: “Oh! The Tate is full of these commercialised horrors, sentimental sob stuff and misapplied technique gone mad, wonderfully painted but oh so sickly!”

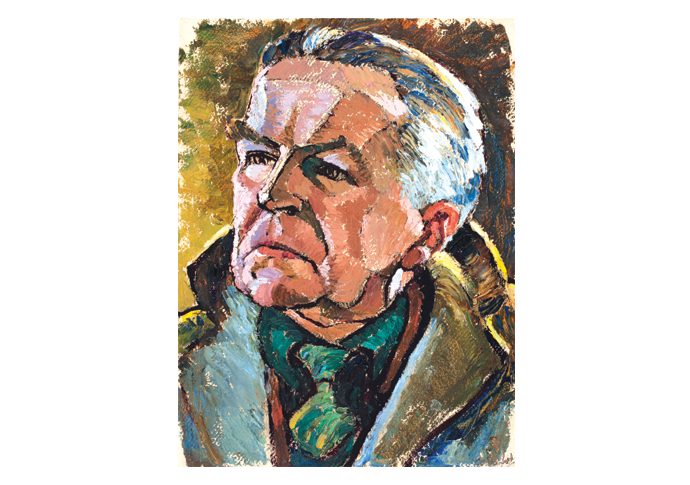

Sybil Andrews: Cyril Power, c1939. copyright Glenbow Museum, Calgary

Uglow said: “At that point they were just searching to find a mode of their own that they felt suited the new, modern age. They were concentrating on form and line, turning against established artists and rejecting detail and realism and any form of ‘picturesqueness’.”

Linocuts, a small yet significant corner of avant-garde art between the wars, became a craze, their clear lines and bright colours shining out against the darkness of the Depression.

They both joined Heatherleys art school, then in Newman Street, Fitzrovia, Sybil full-time and Cyril for only two days a week, filling his sketchbooks with life studies, and fitting the classes in with his architect’s work. He was cooler, less admiring, while Sybil lapped everything up, flinging herself into the work and the spirit of the place.

They finally went their own ways in 1943. He returned to Dolly, who apparently willingly accepted him back. Sybil married and immigrated to Canada in 1947. She roundly denied that she and Cyril were lovers. Uglow writes: “And who can deny her the right to possess the facts of her own life? There are many kinds of couples. If this story is, in the end, a love story, it may not be the kind we expect.”

All the letters that they wrote to each other over the years have disappeared, burnt, destroyed, lost. “I have a vision of smoke rising from braziers in back gardens, scorched pages fluttering and curling, handwriting vanishing into air,” Uglow writes.

Interest in the couple has been growing, with an exhibition at the Osborne Samuel Gallery in Mayfair last year. The couple also featured strongly in an exhibition of modern prints at the Metropolitan Museum in New York recently.

Cyril died aged 78 in 1951. Sybil died aged 94 in 1992.

• Sybil and Cyril Cutting Through Time. By Jenny Uglow, Faber, £12.99