Strummer in the city

On this week’s virtual ramble, Diary drops in at the Clash icon’s favourite boozers, does a lap of Paddington Rec, and discovers the roots of Carnival

Friday, 15th May 2020 — By The Xtra Diary

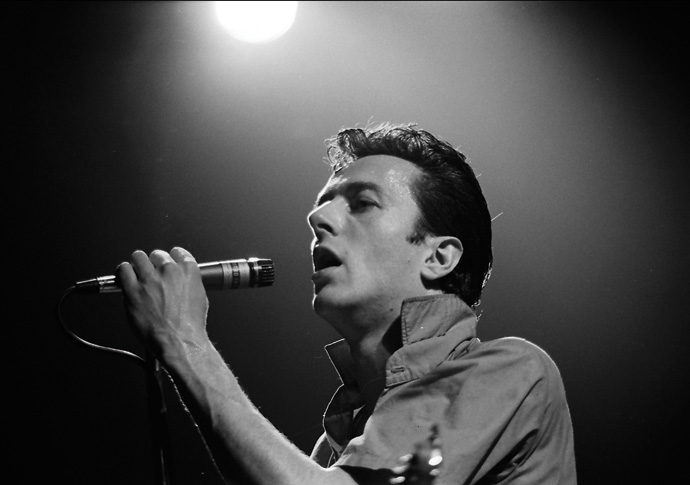

The Clash frontman Joe Strummer, who lived in a Walterton Road squat. Photo: John Coffey

HELLO, friends! Whatever your current status – locked down or footloose and fancy free – join Diary once more to continue our virtual walk through Westminster streets.

We paused our stroll at Edbrooke Road Gardens last week, and now shall continue our tramp in a westwards direction, joining the Elgin Avenue just beyond Paddington Rec, where Sir Roger Bannister ran lap after lap of a cinder track as he trained to beat a four-minute mile in the early 50s.

Artist Edward Ardizzone made Elgin Avenue his home in the 1920s, and when not illustrating children’s books, he could be found sketching the interiors of the area’s pubs on anything that came to hand. These jottings would eventually become the subject of a book, The Local, published in 1939, a celebration of the great Victorian gin palaces of London.

One such boozer was the Chippenham Hotel in Shirland Road, where Ardizzone would find a chair in the saloon bar. Over a pint of mild, he would get down the characters slinking in for refreshment.

37 Cambridge Gardens

Its first licensee was a William Pullen, who had his name above the door in 1881 and the place had done a good trade until the 2010s. Its interior was admired by Ardizzone – period mirrors and tiling were uncovered after a refurb in the 1970s.

And around this time, Clash frontman Joe Strummer was living in a squat round the corner in Walterton Road.

He was in a band called the 101ers, named after the house number of the squat they resided, and they had a weekly gig at ‘The Chip’.

But neither Joe nor Edward would recognise it today: The Chippenham was sold by Punch Taverns to a firm based in an offshore tax haven around six years ago – closed down, its interior stripped out, and threatened with demolition in 2018.

On this sad note, let us stroll past Strummer’s squat until we hit Harrow Road, and take note of another one of Strummer’s haunts, the Windsor Castle pub: it is said The Clash’s song Protex Blue is named after the type of condoms in the gents’ vending machine. The Castle also played host to the likes of Madness and Dexys Midnight Runners, while Iron Maiden showed up and refused to play as the pub was empty – leading to a furious row with the landlord and the heavy metal rockers being banned for life.

From screeching guitars and feedback-saturated amps, we’re moving into warmer bassline territory as we leave Harrow Road behind us and hit Ladbroke Grove – original Carnival territory.

Carnival

While Carnival legend Claudia Jones – the civil rights-battling, USA-baiting, writer, philosopher and seasoned Communist firebrand – is rightfully given dues for establishing the event at the end of the 1950s, it was the work of others that laid the foundations for the biggest street party in Europe.

Jones had organised the first carnivals indoors at St Pancras Town Hall – but in 1964, Ladbroke Grove-based social worker Rhuanne Laslett put on a street party for children whose parents could not afford to take them on holiday.

It had nothing to do with Caribbean culture, merely something for the neighbourhood’s youngsters to do. Attractions included a donkey and cart lent by a trader at Portobello Market and box of false moustaches.

And also there that day was the Russell Henderson Steel Band, a trio led by Henderson, a Trinidadian musician. Their pans hung around their necks and as the day wore on, they decided to remove the barriers at one end of the street and take the children for a walk as they played.

“Although this was only a children’s fete, it still had quite a carnival flavour, so I’m thinking like a carnival in Trinidad, we should have a road march,” Russell told author Lloyd Bradley in an interview more than 40 years later.

Off they went – and on, and on, gaining followers… they ended up looping through the entire neighbourhood in what would be the longest carnival route in the history of the annual pavement rave-up.

Let us follow the ghosts of these pioneers, until we reach Cambridge Gardens – and here we shall pause for another brief consideration of a key moment in Carnival history. As with much of the area in the 1970s, the white stucco housing had been split up into flats: the vast majority were run down, and many were still occupied by squatters.

It was outside number 37 that the Jay brothers turned up in 1980, knocked on the door and told the occupiers they would be setting up their home-made sound system – then called Great Tribulation – in the garden for Carnival. They offered the yawning, dressing gown-wearing, stoned hippies on the doorstep £10 for electricity and said they could make a few bob by selling beers, too.

Norman and Joey Jay played a mixture of reggae, soul, disco and funk – and it was the beginning of the Notting Hill institution, the Good Times Sound System.

And it is here we will pause for another week, to sit on the garden wall of number 37, sup a Red Stripe and gather our thoughts.

Until next time. Stay safe.