Truman and the A-bomb

How did President Harry S Truman reach his decision to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945? It wasn’t his biggest decision, it was just a big bomb, he told Daniel Snowman

Thursday, 7th September 2023 — By Daniel Snowman

President Harry S Truman; inset Daniel Snowman

IN 1963 I was a postgraduate student at Cornell University in the USA completing an MA thesis on presidential decision-making and, in particular, Harry Truman’s to drop the atomic bomb. During my research I contacted Robert Oppenheimer and interviewed several of his atomic scientists and many of the political figures of the time – culminating in a substantial conversation with Truman himself. We met in the presidential library in Independence, Missouri.

Truman turned up in a lightweight, loose-fitting, blue-and-white striped cotton suit that gave his 79-year-old tummy plenty of room to expand. He looked at me with an open-mouthed, jaw-protruding grin as though slightly amused by my temerity. We shook hands and he beckoned me to sit down.

I told him, with what I took to be appropriate respect, that I had been studying American politics at Cornell and his immediate riposte was that I “should’ve come and learned it out here ringing doorbells. They know more about politics out here than in those big East Coast schools,” he grinned.

My particular project, I continued, had been a study of presidential decision-making and, in particular, his decision to drop the atomic bomb. He broke through my deferential manner with a further guffaw.

“That was no decision!” he said, demolishing with a single pre-emptive strike the entire basis of my thesis.

Truman, who had become president barely four months before Hiroshima upon the death of Franklin D Roosevelt, had been convinced by FDR’s advisers that dropping the atomic bomb on people was the one initiative that might bring the war in the Pacific to a rapid end without the need for a protracted and bloody invasion of the Japanese islands, which might have cost a million lives.

“That’s all the atomic bomb was,” he emphasised. “A big bomb to end the war. And it did end it too! I had given the Japanese a warning of what we were going to do and received a sassy reply. They knew what was coming, and it came.”

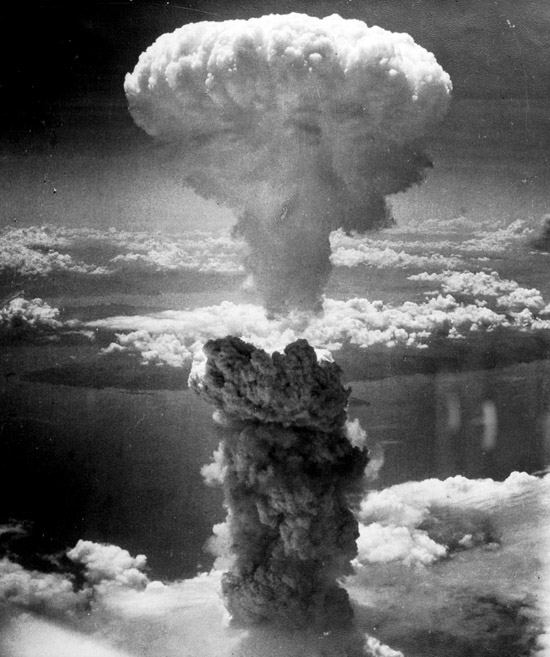

The mushroom cloud from the atomic bombing of Nagasaki, Japan, on August 9, 1945

As I understood it, the USA at the time had manufactured only two atomic bombs: the Uranium-235 “Little Boy” bomb, dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, and the plutonium “Fat Man” bomb dropped on Nagasaki three days later.

“We had lots of ’em,” Truman told me with another wicked grin.

“Did you? I know you said they’d rain upon the Japanese if they didn’t surrender, but I thought that was just to frighten them.”

“Well, once the first one was made, others could be easily constructed.”

I asked about the secrecy that had surrounded the Manhattan Project. During the war, before his nomination as FDR’s vice-presidential running mate in 1944, Missouri Senator Truman had been Chairman of the Senate’s Special Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program. He had been asked not to send investigators into certain war plants, he told me. But, he added confidentially: “I knew about the Manhattan Project!”

Did Truman really know about the Manhattan Project before becoming president? Or was I hearing a combination of bravado, hindsight and the right of the elderly to embroider the facts?

After a few complimentary remarks about Churchill and various other European contributions to the atomic bomb project, especially those of émigré physicists, it was time for another Truman squib.

“Of course, the dropping of the bomb wasn’t the biggest decision I had to make as president.”

“But surely it had the biggest effect.”

“No. It wasn’t the biggest or the most important. The biggest decision was to go into Korea.”

I reflected that I had obviously chosen the wrong topic for my thesis and should have picked on the 1950 intervention in Korea! How, I wondered aloud, does a president reach a decision of such importance?

“You simply look at the facts,” Truman told me. “Nobody had access to all the facts except the president.”

“True. But on many issues, you must have had doubts. You’d come to a decision, change your mind, wonder whether all the information before you was accurately reported and so on?”

“Yes, of course. But I’d check up on the facts, and then come to a decision – and then go on to the next one. I never lost any sleep over any decision I had to make.”

And that clearly included the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. By now emboldened, I told Truman I had always had visions of the US president pacing the corridors of the White House, like Lincoln during the Civil War, weighed down by the pressure of the job.

“I was never under any pressure in the White House,” he answered dismissively. My scepticism must have shown, for Truman leaned forward and added: “Your Winston Churchill was the same, you know.”

Clearly, this was a man keen to appear decisive, even unreflective, the man who famously told people that “if you can’t stand the heat, keep out of the kitchen”.

It was almost as though he thought that weighing the pros and cons was a sign of indecisiveness, of weakness – something of which President Kennedy was at the time being frequently criticised.

Truman at his desk with ‘The Buck Stops Here’ sign

A great many decisions, Truman told me, have to be made by the president and by him alone. I mentioned the famous motto on his desk: “THE BUCK STOPS HERE.” Did he acquire that attitude in the White House?

“Nope. Why, I ran this county the same way years ago!”

He smiled as my questions proliferated. “It’s nice that you youngsters are able to think about these things long after the event and decide what should or shouldn’t have been done at the time!”

All discussion about, for example, whether the bomb was really used to impress or scare the Soviets or about the potential dangers of nuclear radiation was dismissed as the speculations of people who had nothing better to do than debate matters which they weren’t competent to judge.

As far as Truman was concerned, the bomb was intended to end the war with minimum loss of life (that is, no American loss of life) – and it did so.

Eventually it was time for me to go and the old man, warm but provocative to the end, pulled his portly frame out of his seat, shook my hand and waved me a cheery goodbye.

I returned to my hotel and straight away wrote down, as accurately as I could recall, precisely what had been said. Next day, I sent a telegram to London to congratulate my cricket-loving father on his 50th birthday:

“WELL BATTED FOR HALF CENTURY. STOP. HARRY SENDS REGARDS.”

My parents later told me they were thrilled with the telegram but found “Harry” a mystery. In some ways, so did I.

• Daniel Snowman is a social and cultural historian. Since 2004 he’s been a senior research fellow at the Institute of Historical Research, University of London.