Untold stories of forgotten children

Exhibition explores ‘poverty, love and hope’ through the lives of African and Asian children whose mothers turned to the Foundling Hospital

Tuesday, 18th October 2022 — By Jane Clinton

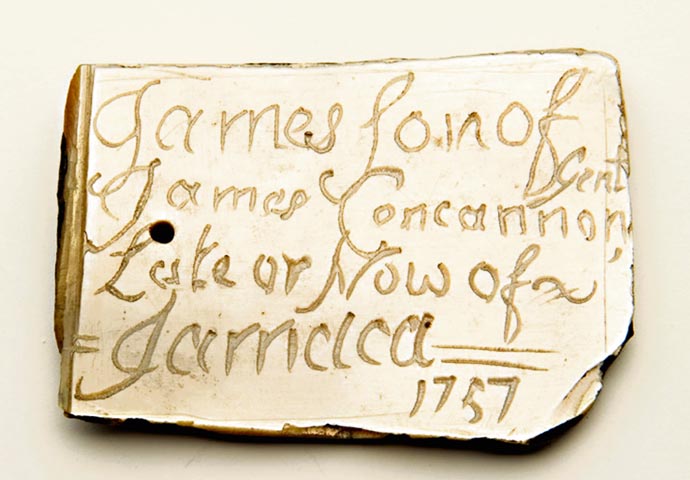

Above: Mother of pearl token – between the 1740s and 1760s, mothers would leave a small object with their baby for identification, should they one day be able to reclaim their child. (Purchased for the Foundling Museum by William and Helena Korner, 2005)

THEY were the forgotten children. African and Asian foundlings whose stories, it seemed, had died with them. Over the years there were fleeting, tantalising glimpses of their existence in official records, but very little else.

Now a new exhibition at the Foundling Museum is bringing these fragments to life as well as painting a picture of London in the 18th century. Until now, researchers had made accidental discoveries of references to African and Asian children in the Foundling Hospital. After three years of research into its archive by exhibition curator Hannah Dennett, we are now able to bear witness to these untold stories through official documents, art from the period, contemporary art and other artefacts.

We follow the lives of some of these children taken into the Foundling Hospital’s care specifically for the period from its opening in 1741 to 1820. During this time there were an estimated 10,000 to 15,000 African people, both free and enslaved, living in Britain. There was also a growing Asian population, including women brought to Britain by returning East India Company officials. Some of these women referenced in the exhibition may have engaged in relationships with men, others had been raped. Some fell pregnant.

Scared and in a foreign country, they had the added barrier of little or no command of English and sought help from the Foundling Hospital.

As the exhibition notes: “These stories of abandonment, poverty, love and hope, stretch thousands of miles across the British Empire.”

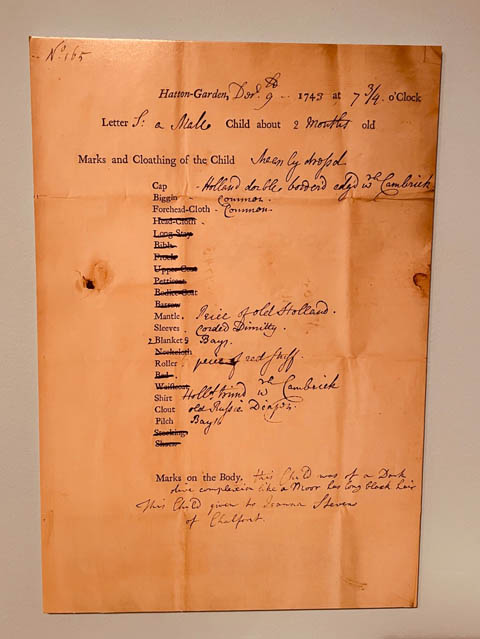

Billet for Miles Cooke, dated 9 December 9 1743, notes he was about two months old and ‘was of a dark olive complexion like a Moor has long black hair’. © Coram

We are introduced to more than a dozen children in the exhibition including Miles Cooke and Christopher Rowland. Sometimes the only clue to their heritage is in the reference to skin colour in the crude (and now offensive) language of the day inscribed in the hospital’s admission records. Miles was just two months old in 1743 when his mother sought help from the hospital. The records state: “This Child was of a dark olive complexion like a Moor has long black hair.”

Aged seven he caught and survived measles. Then aged 11 he was apprenticed into the sea service.

Christopher was brought to the Foundling Hospital aged one month in 1773. His mother Lucy Strange was born in the East Indies (probably India or the Indian subcontinent at that time). She had been sent to England by her master, with the care of his child, but she became pregnant on the voyage. She didn’t speak English and didn’t know the name of the father of the child, so she couldn’t give any more information. She had to return to her master in the East Indies within a few weeks and had no means of supporting a child, so she turned to the Foundling Hospital for help.

“Very many of the women who came seeking help were in domestic service,” explains Kathleen Palmer, Curator: Exhibitions & Displays at the Foundling Museum. “That was the primary work for working class women at the time.”

She adds of Lucy Strange’s case: “There are lots of questions. It says on the voyage she was debauched, but there’s no further detail. There are women who directly recount that they’ve been raped, but it’s not universal. Sometimes it’s a seduction, sometimes it’s a consensual relationship. Sometimes they were promised marriage and the man ran off. There are many different stories.”

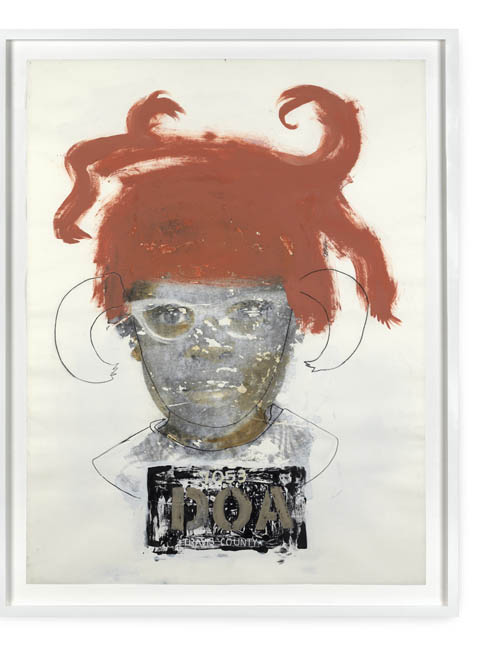

Above: Deborah Roberts’ Little Debbie (Bleached) appears in the exhibition at the Foundling Museum. © Deborah Roberts. Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London. Photo by Todd-White Art Photography

Unfortunately, the faces of these children will never be known to us. Instead loaned work by contemporary artists are included to run parallel with the exhibition as if in dialogue with the children’s stories.

While African and Asian people had lived in Britain continuously since the 16th century, particularly in London, during the 18th century Britain’s expanding empire caused these populations to grow. Echoes of empire can be found running through the exhibition.

Between the 1740s and 1760s, mothers who had brought their child to the Foundling Hospital would leave a small object, a “token” with their baby for identification, in case one day they were able to reclaim their child.

A metal token seal decorated with the head of an enslaved man, showing how slavery permeated everyday life (Purchased for the Foundling Museum by William and Helena Korner, 2005)

One mother left a mother of pearl token. Its inscription refers to “James Concannon Gent” of Jamaica and is dated 1757. It is likely this man was working in the sugar industry or providing military support to plantation owners.

As the exhibition attests, the Foundling Hospital “was part of the fabric of empire, through both its Governors and the African and Asian children, who alongside their fellow foundlings grew up to become Britain’s sailors, soldiers and workers.”

The wealth of many of the male governors also had roots in Britain’s colonial activities.

“We felt it was important to look at where their wealth was coming from and how that underpinned the work of the Hospital,” says Ms Palmer.

The hope is that this exhibition will kickstart further investigation, looking beyond the 18th century to the children admitted to the hospital in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Ms Dennett says: “Tiny Traces addresses a gap in our knowledge of an important part of London’s history – it’s always been there, but never told. This is our history, and I’m delighted that we can share it.”

• Tiny Traces: African & Asian Children at London’s Foundling Hospital runs until February 19 2023 at the Foundling Museum, Brunswick Square. Open Tuesday-Saturday 10am-5pm; Sunday 11am-5pm. Admission charge, but concessions available. Check opening hours at www.foundlingmuseum.org.uk 020 7841 3600.