Review: I Seek A Kind Person by Julian Borger

Michael Church is moved by Julian Borger’s heart-rending history of his father, a man whose past in Nazi Vienna only came to light decades after his suicide

Thursday, 22nd February — By Michael Church

Young Robert with his parents Erna and Leo Borger in Austria in the early 1930s before they resorted to advertising in the Manchester Guardian for a ‘Kind Person’ who would keep him safe from the Nazis

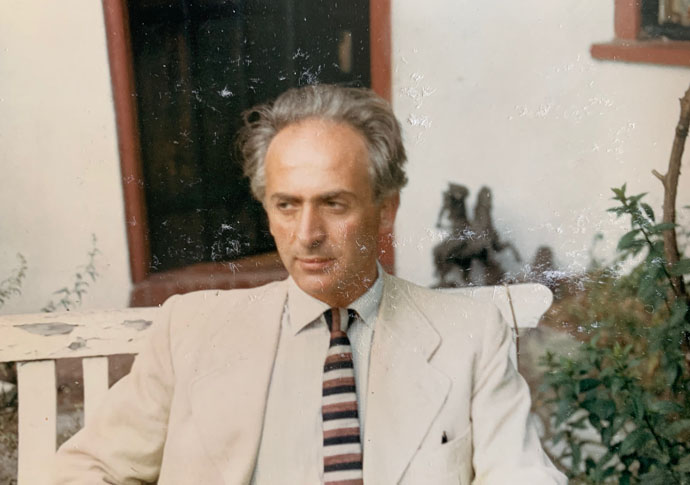

JULIAN Borger’s riveting book starts with a family tragedy narrated with clinical precision. Viennese-born psychologist Robert Borger – described by Julian, his eldest son, as a “serious, melancholic man” – took his own life.

As his thunderstruck wife Wyn and their four children delivered the shocking news to relatives and friends, their assumption was that disappointment at work, plus the humiliating discovery of an adulterous parallel relationship, had triggered his deed.

Robert Borger was a brilliant and rather dictatorial outsider, who wanted to project bourgeois Britishness, and whose unfulfilled professional ambitions led him to slave drive his children academically. And he’d left a suicide note in which he blamed himself for being a failure. Not mentioned in it, however, was anything about childhood traumas.

Yet as a Jewish 11-year-old he had been encouraged by his parents to flee Vienna, alone, in 1938. He rarely talked to his wife and children about his shadowy Viennese past.

It was only much later that the Welsh foster-parents who lovingly looked after him during the war recalled his terror when told he must report to the local police station (in Nazi Vienna that could mean a death sentence).

They also noticed how panicky he got at the sound of their whistling kettle, which reminded him of the whistles of the Nazi Brownshirts chasing him through the streets.

But the full terror he endured in 1938 – at one point locked by Nazis in a synagogue, at another hiding for five days in a cellar – only came to light decades after his death.

Unapprised of all this, Julian Borger and his siblings felt they were almost living with a stranger.

This saga could have made a book in itself, but it’s just the frame for an infinitely wider narrative which Julian found himself writing, partly thanks to a remarkable series of coincidences, and partly to his investigative gifts.

He had always had a vague memory of being told by his mother Wyn that Robert’s parents had advertised him in the classified ads of the Manchester Guardian (now the Guardian), in an attempt to get him safely out of Nazi-ruled Vienna.

And one day Julian decided to check that out. And there it was, in a cutting in an archive, with key words capitalised: “I Seek a Kind Person who will educate my intelligent Boy, aged 11, Viennese of good family. Borger, 5/12 Hintzerstrasse, Vienna 3.”

This was one of seven ads in the “Tuition” section of one day’s paper. “FERVENT prayer in great distress…” began one. “Two very modest sisters, aged 14 and 17, Jews, half orphans, well trained, pray to be accepted as foster children,” began another.

Faced with these “telegrams from another age”, Julian felt impelled to discover what had happened to them all. He decided to track down and interview any survivors (in the event there was just one), and if possible their children. He mined family memories and explored memoirs, websites, and archives in many parts of the world. And thus evolved a history of the Holocaust viewed from an unexpected angle.

His research vividly conjured up Vienna’s darkening atmosphere in 1938, with Jews seriously discussing the pros and cons of suicide as they watched friends being deprived first of their rights, then of their possessions, then of their lives.

A recurring theme was the need to survive economically in exile: Julian’s grandfather – a prosperous shop-keeper – hid gems in his heels, and learned the hairdressing trade; highly educated teenage girls learned the skills necessary for domestic service, and hurriedly learned English.

Robert Borger in later life in London

Devoting each chapter to a particular family, with copious photos dropped into the text, this author allows us to feel we know his dramatis personae, and his book is punctuated by half-glimpsed horrors.

We read of children thinking they were setting off for safety, but were actually destined for what one survivor described as “slow orphan-hood” – the dawning realisation that the parents who’d waved them off at the station had almost immediately afterwards been incinerated, or taken into the woods and shot. One poignant discovery Julian made was his seemingly irrepressible great-aunt’s unspeakable secret – that her stepson had been tortured to death for being a member of the Austrian Resistance.

It was not all tragedy. Some young refugees successfully found refuge in America, others did so in the “Little Vienna” of Shanghai, while yet others cheated death in miraculous escapes.

The most remarkable story concerned the brothers Fred and Frits Schwarz who passed through Auschwitz, Terezin and Birkenau, crossing and re-crossing borders, escaping and getting recaptured, but finally living to tell a tale which Fred turned into a book which he spent the rest of his life reading to schoolchildren.

The story of Robert himself had a desperately sad final twist. Shortly before resorting to the whisky and painkillers which would kill him, he drove to the house of the one person who still remembered him as Bobby, the Jewish boy from Vienna. But that person had gone away.

Had she been at home, Julian muses, might she have talked him out of his fateful plan?

Julian brings his own story full circle with a scrupulously clear-eyed judgment: “The writing of this book unearthed my resentment of [Robert], but also brought its antidote. The lives of those advertised alongside him taught me things about him.”

This is a book written in letters of fire, and as a lifelong friend of the Borger family – with many convivial memories of Robert – I found it very moving. It’s hard to imagine any reader not finding themselves compelled to follow every detail of these enthralling – and sometimes heart-rending – histories.

• I Seek a Kind Person: My Father, Seven Children and the Adverts that Helped Them Escape the Holocaust. By Julian Borger, John Murray, £20